Dopamine anchoring solves both problems by correcting timing and keeping the reward clean:

- The reward comes after effort, not before

- The reward is small enough to be satisfying, but not so big that it derails you

- The sequence repeats until the brain expects follow-through as the normal outcome

If you are competent but inconsistent, it is rarely because you are lazy. More often, it is because your brain has learned that effort does not reliably pay off. Dopamine anchoring rebuilds that trust, one repeatable loop at a time.

The three parts of a dopamine anchor

Every effective dopamine anchor has three parts.

- The Effort Block

A short, clearly defined unit of work. Most people fail because the “work” is vague and endless. - The Reward Signal

A small reward that is immediate, predictable, and does not hijack you. - The Closure Cue

A clear ending that tells your brain: we completed the cycle.

This is the missing piece for many people. If there is no closure, the brain does not register completion. No completion means weaker learning.

The dopamine anchoring rule that changes everything

Consider adjusting the work to be more manageable than your current level of resistance

If you set an effort block that is larger than your current capacity, your brain predicts failure. That prediction creates a sense of threat, which in turn hinders motivation.

Your first job is not to be impressive. Your first job is to be consistent.

Consistency is how you earn trust from your own nervous system.

How to choose rewards that actually work

A reward works when it is

Immediate

Repeatable

Small

Non-addictive

Not disruptive to focus

Here are examples of clean rewards:

A short walk outside

A cup of tea or coffee that you genuinely enjoy

Two minutes of stretching or mobility

One song you love (one song, not a playlist)

A quick check-in text to a friend

A five-minute “sunlight break” by a window

A small visual progress mark (a check, a sticker, a tally)

Here are rewards that often backfire:

Scrolling

Sugar binges

Online shopping

Anything that turns into “just one more.”

Anything that makes it harder to return to the next focused work session is a distraction.

Dopamine anchoring is about training, not escaping.

The dopamine anchoring ladder

The dopamine anchoring ladder is a simple way to match your effort block to your current nervous system capacity. Most people fail because they pick an anchor that is too advanced for their level and then interpret that mismatch as “I have no discipline.” In reality, you just chose an effort block that your brain predicted it could not sustain.

Think of the ladder like strength training for motivation. You do not start with the heaviest weight. You start with the weight you can lift consistently, then you scale.

A key rule before you choose a level: your anchor is only working if you can repeat it without a debate. If you need to inflate yourself, negotiate, or “wait to feel ready,” your anchor is too large, and you should consider stepping down.

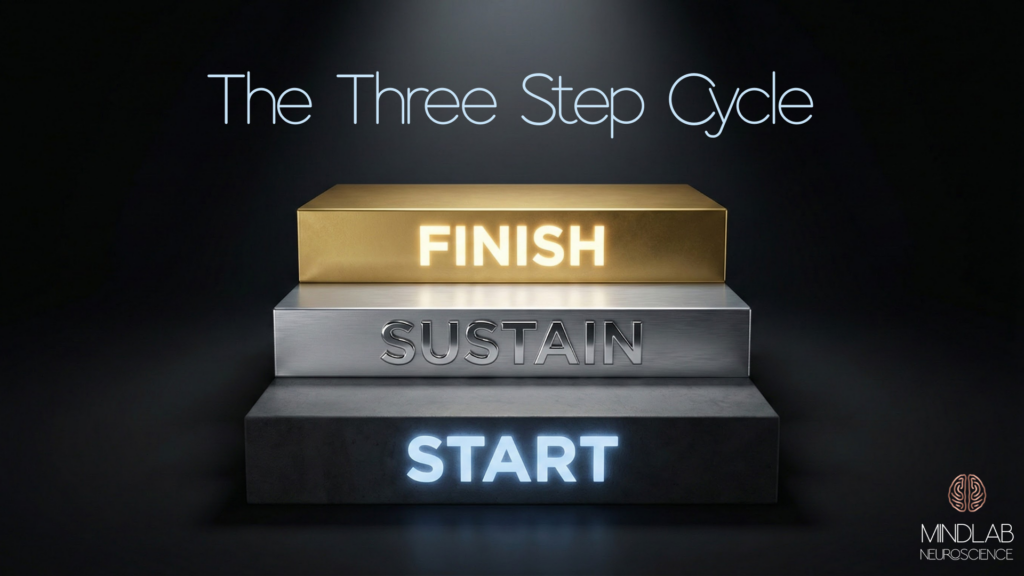

Level 1: Start anchors

Purpose: get you to begin, especially when you feel resistance.

Effort block: 2–5 minutes (sometimes even 60–90 seconds).

Reward: immediate and tiny.

Closure cue: quick, clear, and consistent.

Start anchors are for the person who keeps circling the task but cannot enter it. The only goal here is to teach your brain: starting is safe, and starting pays off.

Examples

Effort block: open the document and write one sentence.

Reward: one sip of coffee you genuinely enjoy.

Closure cue: put a check mark on paper or in a tracker.

Effort block: put on workout clothes and do 3 minutes of movement.

Reward: one song.

Closure cue: “done” out loud plus a quick tally mark.

Level 2: Sustain anchors

Purpose: keep you going once you start, so you build rhythm and stamina.

Effort block: 10–20 minutes (12 minutes is a strong starting point).

Reward: a short break plus closure.

Closure cue: a clear “end” signal that locks in completion.

Sustain anchors are for the person who can start but fades fast or gets pulled into distraction. The main training target is follow-through without burnout.

Examples

Effort block: 12 minutes of focused work with notifications off.

Reward: 2 minutes of movement or stretching.

Closure cue: close the tab, write the next micro-step, then checkmark.

Effort block: 15 minutes of studying.

Reward: step outside for 3 minutes of fresh air

Closure cue: underline what you finished and physically put the book away.

Level 3: Finish anchors

Purpose: train for completion, not perfection, especially when you are at the “last 10%.”

Effort block: the final portion of a task you usually avoid: proofreading, submitting, cleaning up, and sending.

Reward: more substantial, but still clean and time-bound.

Closure cue: a firm “shutdown” ritual so your brain registers the cycle as complete.

Finish anchors are for the person who produces a lot but leaves things open. Open loops drain dopamine. Completion restores it. This level teaches your brain that finishing is not dangerous, and it creates a reliable “done” signal that prevents procrastination from returning right at the end.

Examples

Effort block: finalize and send the email you have been rewriting.

Reward: a 10-minute walk or a specific relaxing ritual.

Closure cue: shut the laptop, clear the desk for 60 seconds, and mark “sent.”

Effort block: complete the last pass on a project and hit submit.

Reward: a planned meal, a short social break, or a restorative activity.

Closure cue: write “closed” or “submitted” in your tracker and set tomorrow’s start cue.

What counts as a good closure cue

Closure is not optional. It is the neurological “stamp” that tells your brain the effort was worth it. Pick one or two cues and keep them consistent, such as

A check mark in a notebook or habit tracker

Writing one sentence: “The next step is ____.”

Closing the laptop or shutting down your computer

Clearing your workspace for 30–60 seconds

Saying “done” out loud (yes, it matters)

Common mistake: choosing the wrong rung

Most people skip Level 1 and wonder why they never build momentum. If starting is hard, make a start anchor first. Once starting becomes automatic, you earn the right to scale into sustained anchors and finish.

The four-step dopamine anchoring protocol

This is the core method. You can use it for work, fitness, studying, creative projects, and even difficult conversations.

Step 1: Name the effort block

Make it specific and measurable.

Examples:

Write 150 words

Answer five emails

Read three pages

Do 10 minutes on the bike

Organize one drawer

Practice one complicated paragraph on the piano

Step 2: Choose the reward signal

One reward. Short. Clean.

Step 3: Set the closure cue

This can be as simple as saying out loud, “Done.”

Or writing a check mark.

Or closing the laptop.

Or tidying your workspace for 30 seconds.

Step 4: Repeat daily

The brain learns through repetition, not intensity.

In this guide, I will show you how dopamine anchoring works, why it is effective, and how to apply it in daily life.

Dopamine anchoring for focus in a distracted world

Many people think they cannot focus because they lack discipline. More often, they cannot concentrate because their brains have been trained to expect constant novelty.

Novelty spikes attention. That is normal. But when your day is built around novelty, effort starts to feel flat.

Dopamine anchoring rebuilds focus by making effort rewarding again.

Here is a simple focus setup:

Effort block: 12 minutes of focused work

Reward: 2 minutes of movement

Closure: check mark plus a sip of water

Repeat: 3 cycles

Twelve minutes sounds small. That is the point. Your brain needs proof that focus is survivable and worth it.

Over time, you scale up to 20 minutes, then 30.

Dopamine anchoring for procrastination

Procrastination is not a time management problem. It is a threat prediction problem.

Your brain procrastinates when a task predicts:

Failure

Judgment

Boredom

Overwhelm

Loss of freedom

Pain with no payoff

Dopamine anchoring changes the prediction by doing two things:

Shrinking the effort block so it feels doable

Guaranteeing a reward that your brain trusts

Try this today:

Effort block: 3 minutes on the task you are avoiding

Reward: one song

Closure: write the next tiny step on a sticky note

You are not trying to finish the task. You are trying to teach your brain to approach it.

Dopamine anchoring for gym consistency

Many people fail with exercise because they tie the reward to a future body outcome. That is too delayed to train the brain.

Instead, reward the behavior.

Example anchor:

Effort block: 8 minutes of movement

Reward: a hot shower with a specific scent you love

Closure: mark it on a calendar

When your brain learns “movement equals payoff,” it stops negotiating.

Dopamine anchoring for emotional regulation

This is where dopamine anchoring becomes powerful in a deeper way.

Emotional regulation is also a skill learned by reinforcement. If your brain learns that the only ways to feel better are to avoid, numb, or explode, then those behaviors become a repetitive cycle.

You can build an anchor for regulation.

Effort block: 90 seconds of slow breathing, or a short vagal toning practice

Reward: warmth, tea, a short grounding routine

Closure: one sentence in a journal: “I chose regulation.”

You are training a new identity: I am the person who can ride discomfort and return.

The most common dopamine anchoring mistakes

Mistake 1: The reward is too big

If the reward hijacks you, your brain will start chasing the reward, not respecting the effort.

Mistake 2: The effort block is too vague

“Work on my business” is not an effort block. It is a threat.

Mistake 3: No closure

Without closure, your brain does not encode completion.

Mistake 4: Inconsistency

Random rewards create a gambling brain. Consistent rewards create a learning brain.

Mistake 5: Using dopamine anchoring only when you feel good

You build the circuit on ordinary days. That is how it shows up on hard days.

A 7-day dopamine anchoring reset

If you want a clean start, do this for one week.

Day 1: Pick one target behavior

Only one. Not five.

Day 2: Define the smallest effort block

So small it feels almost silly.

Day 3: Choose one clean reward

Make it easy to access.

Day 4: Add closure

Decide on your closure cue and keep it identical.

Day 5: Repeat twice

Two cycles in one day.

Day 6: Increase effort by 10%

Do not double it. Do not prove anything.

Day 7: Review and lock it in

Ask: What made it easier to start? What reward felt clean? Did I close the loop?

This is how you build a motivation system that respects your brain.

Dopamine anchoring and “internal rewards”

At first, external rewards help you build the bridge. Over time, the internal reward grows.

Internal rewards are signals like

Pride

Relief

Competence

Clarity

Momentum

Identity reinforcement

You start to feel good because you did the thing, not because you received the reward.

That is the goal.

A helpful transition step is to pair a small external reward with a short internal reflection:

“I started when I did not feel like it.”

“I kept my promise to myself.”

“I am becoming consistent.”

That reflection is not cheesy. It is reinforcement.

Dopamine anchoring for high performers

If you are a high performer, your most significant risk is making effort blocks too large and rewards too rare.

Your brain is not impressed by your ambition. Your patterns train your brain.

High performers often need dopamine anchoring most when:

They are successful but numb

They are productive but inconsistent

They are driven but secretly exhausted

They keep raising the bar and losing the joy

Dopamine anchoring brings you back to a fundamental truth:

The brain performs best when effort is paired with a predictable reward and enough recovery.

Where dopamine anchoring fits inside neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity is your brain’s ability to change through experience.

Dopamine helps decide which experiences get stored as “important.” That is why dopamine anchoring works so well for behavior change. You are using the brain’s learning rules instead of fighting them.

When you repeat the same effort-reward-closure cycle, you are not just building a habit. You are strengthening a pathway.

That is how “hard” becomes “normal.”

Important takeaways and examples of dopamine anchoring

Dopamine anchoring is about training motivation, not forcing it.

Small effort blocks beat big plans.

Rewards should be clean, immediate, and repeatable.

Closure matters because it teaches completion.

Consistency builds trust in your nervous system.

Over time, external rewards can become internal reinforcement.

Your next step

Dopamine anchoring is not a hack. It is a respectful way to work with your brain rather than bully it. If you have been stuck, inconsistent, or exhausted from trying to “push through,” take that as a sign you need a better system, not a harsher inner voice. Your current pattern is not a character flaw. It is a training history.

Here is the hard truth, and also the hopeful one: if you keep rehearsing the same loop, you will keep getting the same result. Insight alone will not change that. Motivation does not arrive first. Momentum does. And momentum is built when your brain gets repeated proof that effort reliably pays off.

Therefore, I encourage you to make the decision today to stop waiting until you feel ready. Pick one behavior that has been quietly costing you time, money, confidence, or peace. Make the effort small enough that your resistance cannot win. Make the reward clean enough that it does not steal your attention. Close the loop so your brain registers completion. Then repeat the same sequence tomorrow, even if you do not feel like it. That’s how you go from “I know what to do” to “I do it.”

Pick one behavior. Make the effort small. Make the reward clean. Close the loop. Repeat.

If you want help building a dopamine anchoring plan that fits your exact brain, schedule, and goals, that is the work I do every day. You do not have to keep guessing your way into consistency or trying to white-knuckle your way through another year. You can train this system with precision, and you can start now.

FAQ: Dopamine Anchoring

How fast does dopamine anchoring work?

Many people feel a shift in a few days because starting becomes easier. Stronger habit wiring usually takes weeks of repetition.

Do I have to reward myself forever?

No. You use rewards to train the pattern. As the brain learns, the behavior becomes more automatic, and the internal reward grows.

What if I “fail” a day?

Consider it as data, not a moral issue. Restart the next day with a smaller effort block. The brain learns by returning.

Can dopamine anchoring help with phone habits?

Yes, but the reward must not be the phone. If the phone is the reward, you train the very loop you are trying to break.

What if rewards feel childish?

Your nervous system isn’t concerned about adult pride. It cares about learning signals. Use rewards as training wheels, then taper.

How many anchors should I build at once?

Start with one. Build momentum. Then add a second anchor when the first feels stable.

Dopamine Anchoring: A Neuroscience Guide to Motivation

Dopamine anchoring is a neuroscience-based strategy that pairs effort with a predictable reward signal, so your brain learns that starting is worth it. If you have ever said, “I know what to do, I just cannot make myself do it,” you are not lazy. You are dealing with a brain that learns through reward.

Most people think motivation is a personality trait. Either you have it, or you do not. That is not how the brain works. Your brain is a prediction machine. It is constantly asking one question: Is the effort worth it?

Dopamine is one of the key chemicals your brain uses to answer that question. Dopamine functions not merely as a “pleasure chemical,” but also as a teaching signal. Dopamine helps your brain tag actions as valuable, repeatable, and worth doing again.

Dopamine anchoring takes that biology seriously. It gives your nervous system a clear pattern: effort, followed by a clean and consistent reward, followed by closure. Over time, your brain stops perceiving effort like a threat and starts viewing it like a path.

As a neuroscientist and the author of my Simon and Schuster book, The Dopamine Code, I care about one thing above all: turning brain science into results you can feel on a Tuesday afternoon when you are exhausted, distracted, and tempted to quit.

A note on The Dopamine Code

When I wrote The Dopamine Code with Simon & Schuster, my goal was not to publish “motivation advice.” My goal was to translate dopamine science into a practical operating system that works in real life, especially for high performers who are smart enough to understand the theory but still struggle with consistency when stress is high and attention is fragmented.

to rewire your brain and create a customized plan

to begin sustained dopamine anchoring.

In the book, I break down how dopamine actually trains behavior through learning, prediction, and reinforcement, and why so many people accidentally wire their brains to associate effort with pressure and reward with escape. That distinction matters because the brain does not change through intention. It changes through patterns that repeat.

If this dopamine anchoring guide feels like it is speaking directly to your experience, that is not a coincidence. It comes from the same framework: take neuroscience seriously, break the steps into small enough chunks to repeat, and build motivation as a circuit you train, not a mood you wait for.

What is dopamine anchoring

Dopamine anchoring is a practical way to train motivation by pairing a specific effort with a specific reward, on purpose, in the same sequence each time. You are teaching your brain that starting and finishing reliably lead to something good, not just “someday,” but now.

It is not bribing yourself. It is conditioning your prediction system, meaning the part of your brain that constantly asks, “If I do this, what happens next?” When the brain cannot predict a payoff, it labels effort as costly and delays action. The brain increases follow-through and decreases resistance when it can anticipate a reward.

Think of an anchor as a stable bridge between:

- The effort you resist

- And a reward your brain trusts

When that bridge is stable, you don’t require motivation to cross it. You cross it because your brain expects the effort to be worth it.

A clean dopamine anchoring sequence has three parts:

- A clear start cue (what tells your brain, “We begin now”).

- A defined effort block (what you do, for how long, and what “done” means)

- A small, immediate reward (something pleasant that does not steal your attention)

Example: 25 minutes of focused work, then 3 minutes of a favorite song, a short walk, or a specific coffee ritual. The anchor is not coffee. The anchor is the predictable order: effort first, reward second, repeated until the brain trusts the pattern.

What dopamine anchoring is not

Dopamine anchoring is not chasing bigger and bigger rewards. That turns motivation into escalation, which is how people burn out. Your brain adapts quickly. If you keep raising the reward, you teach your system that “ordinary effort is not enough,” which makes it harder to start.

Dopamine anchoring is not using a reward that hijacks your attention for an hour after five minutes of work. Doomscrolling, gaming, and endless video clips are not rewards in this context. They create a reward hangover: your dopamine spikes, then drops, and suddenly the original task feels even more boring and painful to return to.

Dopamine anchoring is not forcing discipline through shame. Shame activates threat circuitry. Threat can narrow focus for a moment, but it also makes your nervous system associate effort with danger, which destroys consistency over time. Consistency is the entire point.

Dopamine anchoring is not becoming dependent on rewards. The goal is to build a stable motivation circuit first, then gradually shift the reward from external to internal. Early on, you borrow motivation from a small external reward. Over time, the internal reward becomes a feeling of competence, closure, and momentum.

A simple rule: if the “reward” makes it harder to get back to work, it is not an anchor. It is an escape.

The neuroscience that makes dopamine anchoring work

Dopamine anchoring works because the brain learns through prediction and prediction error, not through willpower speeches.

Prediction is what your brain expects to happen when you take action.

Prediction error is the gap between what you expected and what you actually got.

When the brain experiences a positive prediction error (the result is better than expected), dopamine signals, “Remember this. Repeat this.”

When the brain experiences a negative prediction error (the result is worse than expected), dopamine signals, “Avoid this next time.”

Here’s the motivation trap that many high performers fall into:

- Effort feels expensive right now

- Rewards feel uncertain later

- So the brain predicts: not worth it

Dopamine anchoring changes the prediction in two direct ways:

- It shrinks the time gap between effort and payoff

- It makes the payoff predictable, so the brain stops viewing effort like a gamble

This is not just a mindset. It is reinforcement learning in action. When the effort-reward pairing is consistent, circuits involved in habit and motivation start to automate the sequence. Over time, “start” becomes less of a debate and more of a default.

The key is reliability. The brain does not need a massive reward. It requires a dependable one.

Why smart people still struggle with motivation

Smart, driven people often struggle with motivation for a particular reason: they accidentally train their brain to regard daily effort as unrewarded labor.

A typical hidden pattern is this:

You only reward yourself when you finish something enormous.

It sounds mature, but, neurologically, it teaches your brain that small daily efforts don’t count. Your brain cannot process a future payoff as a reward. It learns from patterns it can sense repeatedly in real time. If the only payoff is far away, the brain becomes stingy with motivation.

The opposite pattern is just as common:

You reward yourself before the effort.

That trains your brain to associate the reward with avoidance, not progress. Then, when you try to start, your brain has already gotten the “hit,” so effort feels even harder because there is no reason to move.

Dopamine anchoring solves both problems by correcting timing and keeping the reward clean:

- The reward comes after effort, not before

- The reward is small enough to be satisfying, but not so big that it derails you

- The sequence repeats until the brain expects follow-through as the normal outcome

If you are competent but inconsistent, it is rarely because you are lazy. More often, it is because your brain has learned that effort does not reliably pay off. Dopamine anchoring rebuilds that trust, one repeatable loop at a time.

The three parts of a dopamine anchor

Every effective dopamine anchor has three parts.

- The Effort Block

A short, clearly defined unit of work. Most people fail because the “work” is vague and endless. - The Reward Signal

A small reward that is immediate, predictable, and does not hijack you. - The Closure Cue

A clear ending that tells your brain: we completed the cycle.

This is the missing piece for many people. If there is no closure, the brain does not register completion. No completion means weaker learning.

The dopamine anchoring rule that changes everything

Consider adjusting the work to be more manageable than your current level of resistance

If you set an effort block that is larger than your current capacity, your brain predicts failure. That prediction creates a sense of threat, which in turn hinders motivation.

Your first job is not to be impressive. Your first job is to be consistent.

Consistency is how you earn trust from your own nervous system.

How to choose rewards that actually work

A reward works when it is

Immediate

Repeatable

Small

Non-addictive

Not disruptive to focus

Here are examples of clean rewards:

A short walk outside

A cup of tea or coffee that you genuinely enjoy

Two minutes of stretching or mobility

One song you love (one song, not a playlist)

A quick check-in text to a friend

A five-minute “sunlight break” by a window

A small visual progress mark (a check, a sticker, a tally)

Here are rewards that often backfire:

Scrolling

Sugar binges

Online shopping

Anything that turns into “just one more.”

Anything that makes it harder to return to the next focused work session is a distraction.

Dopamine anchoring is about training, not escaping.

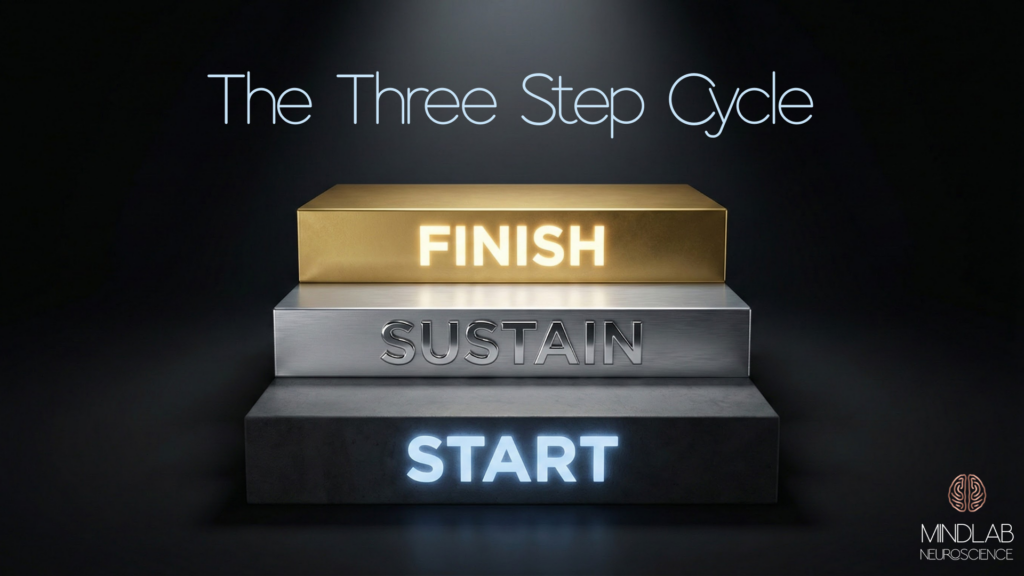

The dopamine anchoring ladder

The dopamine anchoring ladder is a simple way to match your effort block to your current nervous system capacity. Most people fail because they pick an anchor that is too advanced for their level and then interpret that mismatch as “I have no discipline.” In reality, you just chose an effort block that your brain predicted it could not sustain.

Think of the ladder like strength training for motivation. You do not start with the heaviest weight. You start with the weight you can lift consistently, then you scale.

A key rule before you choose a level: your anchor is only working if you can repeat it without a debate. If you need to inflate yourself, negotiate, or “wait to feel ready,” your anchor is too large, and you should consider stepping down.

Level 1: Start anchors

Purpose: get you to begin, especially when you feel resistance.

Effort block: 2–5 minutes (sometimes even 60–90 seconds).

Reward: immediate and tiny.

Closure cue: quick, clear, and consistent.

Start anchors are for the person who keeps circling the task but cannot enter it. The only goal here is to teach your brain: starting is safe, and starting pays off.

Examples

Effort block: open the document and write one sentence.

Reward: one sip of coffee you genuinely enjoy.

Closure cue: put a check mark on paper or in a tracker.

Effort block: put on workout clothes and do 3 minutes of movement.

Reward: one song.

Closure cue: “done” out loud plus a quick tally mark.

Level 2: Sustain anchors

Purpose: keep you going once you start, so you build rhythm and stamina.

Effort block: 10–20 minutes (12 minutes is a strong starting point).

Reward: a short break plus closure.

Closure cue: a clear “end” signal that locks in completion.

Sustain anchors are for the person who can start but fades fast or gets pulled into distraction. The main training target is follow-through without burnout.

Examples

Effort block: 12 minutes of focused work with notifications off.

Reward: 2 minutes of movement or stretching.

Closure cue: close the tab, write the next micro-step, then checkmark.

Effort block: 15 minutes of studying.

Reward: step outside for 3 minutes of fresh air

Closure cue: underline what you finished and physically put the book away.

Level 3: Finish anchors

Purpose: train for completion, not perfection, especially when you are at the “last 10%.”

Effort block: the final portion of a task you usually avoid: proofreading, submitting, cleaning up, and sending.

Reward: more substantial, but still clean and time-bound.

Closure cue: a firm “shutdown” ritual so your brain registers the cycle as complete.

Finish anchors are for the person who produces a lot but leaves things open. Open loops drain dopamine. Completion restores it. This level teaches your brain that finishing is not dangerous, and it creates a reliable “done” signal that prevents procrastination from returning right at the end.

Examples

Effort block: finalize and send the email you have been rewriting.

Reward: a 10-minute walk or a specific relaxing ritual.

Closure cue: shut the laptop, clear the desk for 60 seconds, and mark “sent.”

Effort block: complete the last pass on a project and hit submit.

Reward: a planned meal, a short social break, or a restorative activity.

Closure cue: write “closed” or “submitted” in your tracker and set tomorrow’s start cue.

What counts as a good closure cue

Closure is not optional. It is the neurological “stamp” that tells your brain the effort was worth it. Pick one or two cues and keep them consistent, such as

A check mark in a notebook or habit tracker

Writing one sentence: “The next step is ____.”

Closing the laptop or shutting down your computer

Clearing your workspace for 30–60 seconds

Saying “done” out loud (yes, it matters)

Common mistake: choosing the wrong rung

Most people skip Level 1 and wonder why they never build momentum. If starting is hard, make a start anchor first. Once starting becomes automatic, you earn the right to scale into sustained anchors and finish.

The four-step dopamine anchoring protocol

This is the core method. You can use it for work, fitness, studying, creative projects, and even difficult conversations.

Step 1: Name the effort block

Make it specific and measurable.

Examples:

Write 150 words

Answer five emails

Read three pages

Do 10 minutes on the bike

Organize one drawer

Practice one complicated paragraph on the piano

Step 2: Choose the reward signal

One reward. Short. Clean.

Step 3: Set the closure cue

This can be as simple as saying out loud, “Done.”

Or writing a check mark.

Or closing the laptop.

Or tidying your workspace for 30 seconds.

Step 4: Repeat daily

The brain learns through repetition, not intensity.

In this guide, I will show you how dopamine anchoring works, why it is effective, and how to apply it in daily life.

Dopamine anchoring for focus in a distracted world

Many people think they cannot focus because they lack discipline. More often, they cannot concentrate because their brains have been trained to expect constant novelty.

Novelty spikes attention. That is normal. But when your day is built around novelty, effort starts to feel flat.

Dopamine anchoring rebuilds focus by making effort rewarding again.

Here is a simple focus setup:

Effort block: 12 minutes of focused work

Reward: 2 minutes of movement

Closure: check mark plus a sip of water

Repeat: 3 cycles

Twelve minutes sounds small. That is the point. Your brain needs proof that focus is survivable and worth it.

Over time, you scale up to 20 minutes, then 30.

Dopamine anchoring for procrastination

Procrastination is not a time management problem. It is a threat prediction problem.

Your brain procrastinates when a task predicts:

Failure

Judgment

Boredom

Overwhelm

Loss of freedom

Pain with no payoff

Dopamine anchoring changes the prediction by doing two things:

Shrinking the effort block so it feels doable

Guaranteeing a reward that your brain trusts

Try this today:

Effort block: 3 minutes on the task you are avoiding

Reward: one song

Closure: write the next tiny step on a sticky note

You are not trying to finish the task. You are trying to teach your brain to approach it.

Dopamine anchoring for gym consistency

Many people fail with exercise because they tie the reward to a future body outcome. That is too delayed to train the brain.

Instead, reward the behavior.

Example anchor:

Effort block: 8 minutes of movement

Reward: a hot shower with a specific scent you love

Closure: mark it on a calendar

When your brain learns “movement equals payoff,” it stops negotiating.

Dopamine anchoring for emotional regulation

This is where dopamine anchoring becomes powerful in a deeper way.

Emotional regulation is also a skill learned by reinforcement. If your brain learns that the only ways to feel better are to avoid, numb, or explode, then those behaviors become a repetitive cycle.

You can build an anchor for regulation.

Effort block: 90 seconds of slow breathing, or a short vagal toning practice

Reward: warmth, tea, a short grounding routine

Closure: one sentence in a journal: “I chose regulation.”

You are training a new identity: I am the person who can ride discomfort and return.

The most common dopamine anchoring mistakes

Mistake 1: The reward is too big

If the reward hijacks you, your brain will start chasing the reward, not respecting the effort.

Mistake 2: The effort block is too vague

“Work on my business” is not an effort block. It is a threat.

Mistake 3: No closure

Without closure, your brain does not encode completion.

Mistake 4: Inconsistency

Random rewards create a gambling brain. Consistent rewards create a learning brain.

Mistake 5: Using dopamine anchoring only when you feel good

You build the circuit on ordinary days. That is how it shows up on hard days.

A 7-day dopamine anchoring reset

If you want a clean start, do this for one week.

Day 1: Pick one target behavior

Only one. Not five.

Day 2: Define the smallest effort block

So small it feels almost silly.

Day 3: Choose one clean reward

Make it easy to access.

Day 4: Add closure

Decide on your closure cue and keep it identical.

Day 5: Repeat twice

Two cycles in one day.

Day 6: Increase effort by 10%

Do not double it. Do not prove anything.

Day 7: Review and lock it in

Ask: What made it easier to start? What reward felt clean? Did I close the loop?

This is how you build a motivation system that respects your brain.

Dopamine anchoring and “internal rewards”

At first, external rewards help you build the bridge. Over time, the internal reward grows.

Internal rewards are signals like

Pride

Relief

Competence

Clarity

Momentum

Identity reinforcement

You start to feel good because you did the thing, not because you received the reward.

That is the goal.

A helpful transition step is to pair a small external reward with a short internal reflection:

“I started when I did not feel like it.”

“I kept my promise to myself.”

“I am becoming consistent.”

That reflection is not cheesy. It is reinforcement.

Dopamine anchoring for high performers

If you are a high performer, your most significant risk is making effort blocks too large and rewards too rare.

Your brain is not impressed by your ambition. Your patterns train your brain.

High performers often need dopamine anchoring most when:

They are successful but numb

They are productive but inconsistent

They are driven but secretly exhausted

They keep raising the bar and losing the joy

Dopamine anchoring brings you back to a fundamental truth:

The brain performs best when effort is paired with a predictable reward and enough recovery.

Where dopamine anchoring fits inside neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity is your brain’s ability to change through experience.

Dopamine helps decide which experiences get stored as “important.” That is why dopamine anchoring works so well for behavior change. You are using the brain’s learning rules instead of fighting them.

When you repeat the same effort-reward-closure cycle, you are not just building a habit. You are strengthening a pathway.

That is how “hard” becomes “normal.”

Important takeaways and examples of dopamine anchoring

Dopamine anchoring is about training motivation, not forcing it.

Small effort blocks beat big plans.

Rewards should be clean, immediate, and repeatable.

Closure matters because it teaches completion.

Consistency builds trust in your nervous system.

Over time, external rewards can become internal reinforcement.

Your next step

Dopamine anchoring is not a hack. It is a respectful way to work with your brain rather than bully it. If you have been stuck, inconsistent, or exhausted from trying to “push through,” take that as a sign you need a better system, not a harsher inner voice. Your current pattern is not a character flaw. It is a training history.

Here is the hard truth, and also the hopeful one: if you keep rehearsing the same loop, you will keep getting the same result. Insight alone will not change that. Motivation does not arrive first. Momentum does. And momentum is built when your brain gets repeated proof that effort reliably pays off.

Therefore, I encourage you to make the decision today to stop waiting until you feel ready. Pick one behavior that has been quietly costing you time, money, confidence, or peace. Make the effort small enough that your resistance cannot win. Make the reward clean enough that it does not steal your attention. Close the loop so your brain registers completion. Then repeat the same sequence tomorrow, even if you do not feel like it. That’s how you go from “I know what to do” to “I do it.”

Pick one behavior. Make the effort small. Make the reward clean. Close the loop. Repeat.

If you want help building a dopamine anchoring plan that fits your exact brain, schedule, and goals, that is the work I do every day. You do not have to keep guessing your way into consistency or trying to white-knuckle your way through another year. You can train this system with precision, and you can start now.