🎧 Audio Version

Performance Anxiety, My Background, And Why Your Brain Feels Like It Betrays You

I have spent more than twenty-five years studying the human brain and working with clients whose lives look successful from the outside, yet inside they feel shaky whenever the stakes rise. I have coached hedge fund managers, surgeons, lawyers, founders, performers, and everyday high achievers through intense performance anxiety. At MindLAB Neuroscience, everything I do is grounded in how the brain actually works, not in generic motivational talk.

When your heart races before a big meeting, when your mind goes blank during a presentation, or when your hands shake on a first date, it is easy to think something is wrong with you. You might convince yourself that you are weak, unsuited for this, or that you need to adjust your personality. From a neuroscience perspective, that is not accurate. Performance anxiety is a brain state. It is a pattern that is activated when your nervous system perceives you as under threat.

Your brain is not trying to ruin your chances. It is trying to protect you. The problem is that it often misreads modern situations as life-or-death when, in reality, they are essential but not dangerous. Your nervous system has trouble distinguishing between a boardroom and a cave full of predators. This is one reason performance anxiety feels so intense and physical. The circuits that evolved to keep you alive in a harsh environment now light up when you stand up to speak or open your mouth in a negotiation.

This guide explains how circuits work, why they overreact, and how to retrain them. I will talk about evolution, brain systems, and neurochemistry, but in language that makes sense in daily life. I will share real client stories, with identifying details changed, so you can see how these patterns show up in different careers and relationships. Most importantly, I will show you how to build practical, brain-based routines that reduce performance anxiety rather than feed it.

My goal is simple. I want you to understand your brain well enough that you stop fighting it and start working with it. Once you see performance anxiety as a predictable nervous system pattern, it stops feeling like a mysterious curse and becomes something you can shape with deliberate practice.

How Evolution Wired Performance Anxiety Into Your Brain

To understand why performance anxiety feels so overpowering, you have to go back in time, long before meeting rooms and video calls. For most of human history, survival depended on two things. You had to stay physically safe and socially accepted by your group. Getting cast out of the group meant fewer resources and less protection. To your brain, disapproval from the tribe felt almost as dangerous as a physical threat.

The same core survival systems that helped early humans avoid predators now monitor modern social situations. When you stand to give a talk or sit down for a high-stakes conversation, ancient brain regions scan for signs of danger; they pay attention to faces, tone of voice, and tiny shifts in the room. Your brain triggers an alarm if it anticipates rejection, embarrassment, or humiliation. That alarm is what you experience as performance anxiety.

Your brain did not evolve to care about PowerPoint slides or quarterly numbers. It evolved to care about status, inclusion, and the risk of shame. Losing status in a small group thousands of years ago could mean fewer chances to mate, fewer allies, and less protection. Today, when your boss frowns, an investor crosses their arms, or a partner looks bored, those same circuits fire as if your long-term survival is at risk.

This is why performance anxiety can feel out of proportion to the situation. Logically, you know that stumbling on a sentence in a presentation will not end your life. But the older parts of your brain do not trust that logic. Your brain perceives a crowd of eyes watching you and triggers a fight, flight, or freeze response. Your heart pounds to push blood to your limbs in case you need to run. Your breathing becomes shallow. Your digestive system slows down. These responses made sense when you needed to sprint away from danger. In a modern high-pressure moment, they only make it harder to think clearly.

There is also a second evolutionary piece. Your brain is a prediction machine. It constantly tries to guess what will happen next so it can keep you safe. When you have a painful or embarrassing experience, your brain stores it and assigns it more weight. The next time a similar situation appears, your brain predicts danger even faster. Performance anxiety often grows this way. One negative experience on stage, or in a tough meeting, can teach your nervous system that this type of event is a threat.

The critical point is that evolution did not design you to be calm under every form of social pressure. It is intended that you notice the risk and respond quickly. Once you understand that, you can stop blaming yourself and instead focus on updating old predictions with new experiences.

The Brain Circuits That Drive Performance Anxiety

When clients come to me and describe performance anxiety, they often talk about the symptoms, not the brain systems. They say their mind goes blank, their chest feels tight, or they cannot get words out. Under the surface, several brain regions are working together in ways that make those reactions feel almost automatic.

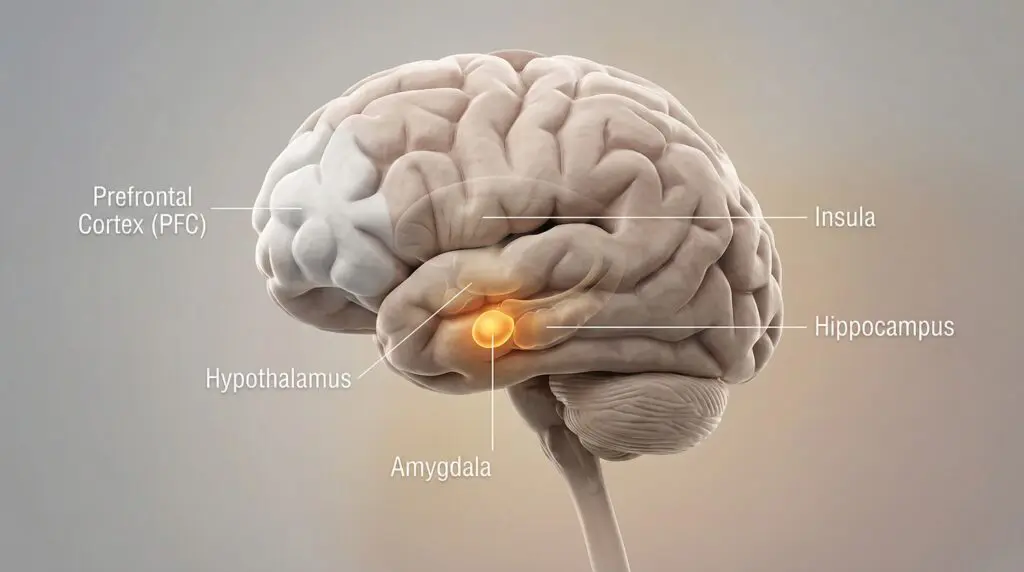

The amygdala is one of the leading players. It sits deep inside the brain and acts like a rapid threat detector. It scans for anything that looks or feels similar to past danger. When the amygdala senses a social or status threat, it sends strong signals to the rest of the nervous system. These signals trigger the stress response and can set off performance anxiety before you are even conscious of what you are reacting to.

The prefrontal cortex, which sits behind your forehead, is the planning and decision-making center. It helps you organize your thoughts, retain information, and decide how to respond. In calm conditions, the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala work together in a healthy balance. The thinking regions can tell the alarm system, “Thank you, I hear you, but this is not really dangerous.” When performance anxiety spikes, that balance flips.

Stress hormones shift blood flow away from the prefrontal cortex and toward older survival circuits. This leads to a physical challenge in retrieving words from memory, recalling your talking points, and making spontaneous decisions. You are not suddenly less intelligent. Your brain is moving into a protective mode that favors rapid reactions over careful thinking. This is why even highly skilled people can feel clumsy or slow when performance anxiety hits.

Another important region is the insula, which maps internal sensations. It tracks your heart rate, breathing, gut feelings, and body temperature. When the insula becomes highly active, you feel more aware of every little internal change. A tiny shift in your breathing can feel enormous. A slight flutter in your chest can feel like a central alarm. Performance anxiety often involves a loop between the insula and the amygdala. You notice a physical symptom, your brain labels it as danger, the alarm grows, and your body responds even more.

The anterior cingulate cortex also plays a role. It monitors errors and conflicts. In high-stakes situations, this region may become hypervigilant, vigilantly scanning for any indication of mistakes. If you stumble on a word or lose your place, this monitoring network can overreact and signal that something is going wrong. Again, performance anxiety can grow from this pattern of hyper-monitoring and self-criticism inside the brain.

Finally, networks that handle social understanding and self-reflection, sometimes called mentalizing and default mode networks, add another layer. They generate thoughts like “Everyone is judging me” or “I look stupid. Those thoughts are not random. They are brain-based predictions built from past experiences and beliefs about your worth. When these networks fuse with the threat circuits, performance anxiety becomes a full-body and full-mind experience.

What Your Body Is Trying To Tell You When Anxiety Spikes

Many of my clients say that performance anxiety feels like their body is turning against them at the worst possible moment. Their hands sweat, their cheeks flush, their voice shakes, and their stomach flips. From a neuroscience perspective, these are not random failures. They are how your autonomic nervous system prepares you for challenges.

The sympathetic branch of this system speeds things up. It increases heart rate, raises blood pressure, and releases stress hormones like adrenaline. This response is useful if you need to move quickly or push through effort. When you are about to speak, perform, or have a crucial conversation, that same sympathetic activation turns on. The problem is that your brain often interprets these signals as proof that you cannot handle the moment.

If you have experienced performance anxiety many times, your brain learns to fear the sensations themselves. Your heart starts pounding, and your mind warns you, “This is going to end badly again.” That thought is not harmless. It changes how your insula and amygdala respond to signals from your body. The sensations are labeled as dangerous rather than simply aroused. This is one reason performance anxiety can grow over time, even if your skill level is improving.

There is another branch of the autonomic nervous system, the parasympathetic branch, which helps you slow down and recover. It is linked to the vagus nerve, which connects your brain to your heart, lungs, and digestive system. When this calming system is active, your heart rate slows, your breathing deepens, and your body feels more settled. In clients with intense performance anxiety, this calming branch is often underused in high-pressure situations.

You can conceptualize performance states as oscillating between these two branches. A healthy response to challenge involves a firm but controlled sympathetic rise, followed by a solid parasympathetic recovery. You feel energized but not overwhelmed. Performance anxiety causes the seesaw to become immobilized. The empathetic side surges, and the calming side does not come online in time. The outcome is a surge of energy that lacks direction.

Learning to work with your body is a key part of reducing performance anxiety. When you understand that your racing heart or shaky hands are just your nervous system preparing you, you can change your relationship to those sensations. Instead of reading them as proof of weakness, you learn to regard them as waves of energy you can ride. This shift in meaning changes how your brain responds and can gradually weaken the old pattern.

These physical and mental shifts are some of the most common symptoms of performance anxiety, even in people who are highly skilled and well prepared.

Real Client Stories Of Performance Anxiety In Action

Stories make the science real, so I want to share a few examples from my practice. We have changed names and details, but the brain patterns are strikingly similar to what many people experience. I see the same brain patterns in athletic performance anxiety, when gifted competitors suddenly feel tight, slow, or disconnected the moment the game or race really counts.

One client, whom I will call David, was a portfolio manager at a hedge fund. His performance anxiety did not show up when he built models or analyzed companies in his office. It hit him when he sat in the weekly risk meeting with senior leadership. Before these meetings, David would wake up with his heart pounding. On the subway, his mind replayed every past mistake. In the conference room, by the time it was his turn to speak, his hands were shaking so much that he avoided picking up his coffee.

From the outside, David looked confident. Inside, his amygdala was firing as if he were standing in front of a firing squad. Early in our work, he told me that as a kid, he had been harshly criticized at the dinner table whenever he said something that sounded foolish. His nervous system had learned the danger of speaking in front of authority figures. These experiences created a strong connection between social evaluation and feelings of threat. His performance anxiety as an adult was a result of his brain attempting to protect him from that past danger.

Another client, whom I will call Mia, was a gifted surgeon. She had trained for years, had excellent technical skill, and did well in most settings. Her performance anxiety appeared when a senior attending watched her operate or when a brutal family member was present during post-surgery conversations. Her hands would stay steady during the procedure, but her thoughts would fill with worst-case images. Her insula picked up every microsensation, and her error-monitoring network went into overdrive.

We traced some of her patterns back to her medical school days, when a professor humiliated her in front of the class over a minor mistake. That one event created a powerful memory. Each time she stepped into a similar environment, her brain predicted the same kind of social pain. Performance anxiety, for her, was not about lack of skill. It was about an overactive prediction system that kept expecting public shame.

A third client, whom we can call Jake, was a young musician. On his own, he played beautifully. In rehearsal with his band, he did fine. When he stepped onto a stage with lights and a crowd, performance anxiety took over. His fingers stiffened, his timing slipped, and he felt like an observer watching himself fail. His brain was caught in a self-focused loop, monitoring every tiny move rather than letting trained motor circuits handle the music. His story is a classic example of performance anxiety in musicians, where the stage, the lights, and the crowd trigger a very different brain state than quiet practice alone.

In all three cases, the root problem was not a broken personality. It was a set of brain patterns shaped by experience and reinforced by repetition. Once we mapped the patterns, we could build targeted training that calmed the alarm systems and strengthened the networks needed for steady performance. These stories show that performance anxiety is common even among competent people. It does not mean you are not talented. It usually means your brain has not yet learned what proper safety feels like in those specific high-pressure situations.

How Performance Anxiety Gets Wired In Through Neuroplasticity

Your brain is not a fixed machine. It constantly rewires based on experience. This ability to change is called neuroplasticity. The exact process that helped you develop your skills can also build or reduce performance anxiety over time.

Each time you face a high-stakes situation, your brain makes predictions, observes what happens, and then updates its maps. If you go into a meeting expecting disaster, feel your heart pounding, and then pull back from speaking up, your brain learns something. It teaches that avoidance reduces your discomfort. The amygdala files that away as a short-term success. Neuroplasticity then strengthens the link between the trigger and the avoidance. The next time, performance anxiety arrives even faster.

This is how a simple nervous moment can turn into a strong pattern. The more your brain repeats the same sequence, the more automatic it becomes. Threat detection fires, uncomfortable sensations rise, your mind tells a scary story, you retreat, and the brain concludes that retreat equals safety. The wiring becomes tighter with every repetition. Neuroplasticity does not care whether a pattern is beneficial or not. It simply strengthens what you practice.

The same principle works in your favor when you change the sequence. When clients start to approach performance anxiety with curiosity instead of panic, new wiring can form. For example, when David stayed in the risk meeting and spoke even while his heart pounded, we helped his brain learn a new lesson. He survived. He was not to be fired. In fact, his ideas were often respected. Each time he stayed with the experience instead of escaping into silence, the amygdala received a different outcome.

Over time, the prediction that these meetings posed danger weakened. The prefrontal cortex gained more influence, and the calming branches of his nervous system learned to come online sooner. Neuroplasticity rewired the pattern. Performance anxiety did not vanish overnight, but it shifted from a tidal wave to a set of manageable waves. Over time, this kind of deliberate retraining is the real path to overcoming performance anxiety, because it teaches your brain that you can stay engaged and safe even while your body feels highly activated.

Mia used a similar process in the operating room and in challenging conversations with families. We trained her to notice the earliest bodily signals, label them, and stay present rather than tightening against them. She learned to redirect her attention from self-judgment to task-focused thinking. Doing this repeatedly in real situations taught her brain that arousal did not mean catastrophe. Her error monitoring network stayed active, which is vital for safe surgery, but it stopped screaming that every small uncertainty was a disaster.

With Jake, we built new rehearsal routines that mimicked the intensity of live performance. We practiced under bright lights, with cameras, with small audiences, and with subtle changes that triggered his nervous system. He learned to let motor circuits run his plays while he gently shifted his attention away from internal monitoring. Subsequent exposure under expert guidance altered his brain’s response to scrutiny. His performance anxiety faded into a normal and even functional level of pre-show energy.

These stories highlight a key truth. Performance anxiety is plastic. It is shaped by your actions before, during, and after high-pressure events. Once you deliberately work with that plasticity, you can begin to sculpt a new pattern.

Why Some People Struggle With Performance Anxiety And Others Seem Immune

One of the questions I hear all the time in my practice is simple and painful. If my brain reacts this way, why do other people seem totally calm under pressure? They walk onto a stage or into a tense room like it is nothing, while your heart feels like it will jump out of your chest.

From a neuroscience perspective, there are several reasons for this. None of them means you are weak, broken, or less capable. They tell your brain and nervous system were shaped by a different mix of biology and experience.

Some people are born with what we call a more reactive temperament. Their nervous system is set to detect danger more quickly and respond more strongly. Even as babies, these children startle more easily, cling more, and have a harder time with sudden changes. Over time, this baseline sensitivity can lead to stronger responses in the amygdala and the body. When the stakes rise, their internal alarms naturally ring louder.

Other people arrive with a calmer baseline. Their amygdala still does its job, but the prefrontal cortex and calming systems step in more quickly and keep the alarms in check. These people are not fearless; they simply have a nervous system that does not jump as high or as fast. Under pressure, they still feel activated, but they stay inside a window where thinking and speaking are easier.

Early experiences also shape who develops intense performance anxiety and who does not. If you grew up in an environment where mistakes were met with shame, sarcasm, or sudden anger, your nervous system learned that being watched is dangerous. When you tried something new and were laughed at, punished, or ignored, your brain stored that as a crucial memory. Later in life, standing in front of a group can trigger the same circuits, even if you are now highly skilled.

By contrast, people who had caregivers or teachers who responded to mistakes with guidance rather than humiliation developed very different wiring. Their error-monitoring networks still detect when they slip, but those signals do not automatically trigger fear. They learned that stumbling is a sign of growth, not impending attack or rejection. That early pattern becomes a quiet form of armor in adult life.

Repetition is another key factor. Someone who has performed, presented, or competed since a young age has given their brain thousands of chances to practice recovery. Their nervous system has seen many examples of rising energy that did not lead to disaster. Each experience becomes a small safety memory. Together, those memories teach the amygdala and body that high arousal can end well.

If you avoided these situations for years or only stepped into them when the stakes were already very high, your brain never got that training. Your first big talk may have been your first time in front of a crowd. This is a significant challenge for any nervous system. When those big early moments do not go well, performance anxiety can grow quickly. Your brain draws firm conclusions from a small number of intense events.

Beliefs and inner language also play a role. People who do not struggle much with these states usually carry different stories about themselves. They might think, “I get nervous, but I figure it out, or I typically warm up once I get going. Those thoughts are not empty affirmations. They are predictions that shape how the prefrontal cortex and limbic system work together. When When the body starts to rev up, the thinking brain sends calming messages to prevent the loop from spinning out of control.

If your inner language sounds more like “I always fall apart” or “everyone is waiting for me to fail,” your brain receives a very different script. Those phrases come from real experiences and old emotional pain, but they also keep the alarm circuits tight and quick. When your heart speeds up, your mind interprets it as the first sign of collapse. That meaning feeds back into the amygdala and creates more performance anxiety.

It is also true that some people who appear calm on the outside have learned to mask what their nervous systems are doing. They do not actually feel as steady as they occur. They have simply built strong habits around breathing, posture, and attention that hide the internal noise. When I work with leaders who seem fearless, they often admit that they still feel surges of energy and doubt. They just have a practiced way of moving through it.

The important takeaway is this. You and the person who seems immune are not different in brain quality. It is that their nervous system has had different inputs and different training over time. Genetics, temperament, early relationships, practice, and belief all shape whether performance anxiety becomes a loud pattern or a quiet hum. Once you understand that, you can stop envying other people’s brains and start giving your own brain the experiences and guidance it never got.

Brain-Based Strategies Before High-Pressure Events

Most people wait until performance anxiety explodes during the event and then try to calm down. In this section, I am going to show you how to reduce performance anxiety by training your brain before the pressure hits instead of waiting until you are overwhelmed.

By that point, the stress chemicals are already flooding the system. A more effective approach is to train your brain in the hours and days leading up to the event. You want to shape the predictions and bodily states that will show up when the spotlight turns on.

The first step is to teach your brain that preparation does not equal danger. Many clients tell me that as soon as they open the slide deck or think about the meeting, their heart starts racing. The amygdala has learned to respond to anything linked to the future event. To shift this, you can break preparation into small, manageable blocks. Spend a short period, even ten or fifteen minutes, reviewing material while intentionally keeping your breathing steady and your body relaxed.

This action sends a new signal to your nervous system. It says we can think about this event without going into full alarm. When you repeat this many times, neuroplasticity begins to connect the content of the performance with a calmer physiological state. You are not forcing yourself to feel wonderful. You are teaching your brain that engagement plus regulation is possible. Over time, performance anxiety has less fuel to burn on the day of the event.

Another brain-based strategy is mental rehearsal, which includes both feelings and details. Your brain uses many of the same circuits for vivid imagination and authentic experience. When you rehearse, picture the room, the faces, the sounds, and your own body, but do so while practicing calm, slow exhalations. Imagine your feet grounded on the floor and your voice steady. You are not trying to create a fantasy of perfection. You are giving your nervous system a preview of success to reference later.

Sleep and recovery matter as well. Chronic sleep debt primes the amygdala to overreact and weakens the prefrontal cortex. When I work with clients who struggle with performance anxiety, we consider sleep as part of their training plan. It is not a luxury. It is a core part of keeping the brain able to regulate under stress. Even one or two nights of slightly improved sleep before a big event can give you a better platform to stand on.

Finally, what you tell yourself leading up to the event changes brain chemistry. If you spend days repeating, “I always mess this up,” your brain will predict failure and prepare for it. If you shift to language like, “My brain gets loud before these events, but I know how to ride that wave now,” you are giving your thinking networks a healthier narrative. That narrative influences how much control the prefrontal cortex has when performance anxiety tries to take over.

Training Your Brain In The Heat Of The Moment

No matter how much you prepare, there will be moments when performance anxiety flares during the event itself. The key is not to chase total calm. Staying in a zone where you can still think, respond, and stay connected to what matters is crucial. This is where real-time brain-based tools come in.

One of the most powerful levers you have is your breath. Fast, shallow breathing signals danger to your brain. Longer, slower exhales signal safety. When clients are in the middle of a high-pressure situation, I teach them to make micro-adjustments rather than dramatic changes. You cannot always pause for a prolonged breathing exercise in front of a crowd. But you can quietly lengthen your exhale by even one second and do that several times.

This slight shift sends a message through the vagus nerve to the brainstem and higher regions. It tells the system it can ease out of emergency mode. Over a few minutes, this mechanism can bring performance anxiety down from a roar to a hum. You might still feel activated, but you regain access to more of your prefrontal abilities.

Attention is another powerful lever. When performance anxiety spikes, your attention collapses inward. You start watching yourself from the outside, judging every word, and imagining what others think. This self-monitoring drains resources from the brain networks needed for the task. A practical way to reverse this vicious cycle is to pick a concrete anchor outside yourself.

When speaking, you can focus on a friendly face or your hand gestures. In a negotiation, you can focus on the other person’s breathing or the words being said. Shifting attention outward does not erase every anxious feeling, but it moves your brain out of the loop of constant self-evaluation. Performance anxiety grows in that self-focused loop. It shrinks when your attention lands on the work at hand.

Another real-time tool is to relabel the sensations. Many clients find it helpful to say to themselves, “This is my brain giving me extra energy,” instead of “This means I am failing.” That small change in language moves you from fear of the sensations to ownership of them. Your insula and cognitive networks work together to give the bodily signals a different meaning. Over time, that new meaning becomes the default, and performance anxiety loses some of its bite.

Everyone stumbles, but how you respond to those few seconds is more important than the actual stumble. The error-monitoring network will notice and send a signal. You cannot stop that. What you can do is avoid adding a second wave of self-attack. A short, simple reset, such as taking a breath and saying, Let me say that another way,” gives your brain a template for recovery. This technique keeps performance anxiety from ballooning after small mistakes.

What Naturally Calm High Performers Get Right At The Brain Level

There is another angle that helps build absolute authority on this topic. Throughout my tenure at MindLAB Neuroscience, I have not solely assisted individuals plagued by performance anxiety. I have also studied people who stay remarkably steady in situations that would rattle almost anyone. Elite traders who make split-second decisions with millions on the line, surgeons who stay composed during complex procedures, and founders who field harsh questions in public without losing their center.

On the surface, they look fearless. Under the surface, several brain-based habits set them apart. These habits are not magic, and they are not reserved for a lucky few. They are learnable patterns you can begin adopting.

First, naturally calm high performers do not confuse arousal with danger. They feel their hearts race and their breathing change, just as anyone else does. The difference lies in how they interpret those sensations. Instead of thinking, “This means I am about to fail,” they think, “My body is preparing to assist me.” This mental frame is not a trick. This mental frame alters the way the insula and higher-order thinking regions interpret signals from the body. The same physical energy that would feed performance anxiety in one person becomes fuel for focus in another.

Second, these people have trained their attention like a muscle. When the stakes rise, they do not let their focus collapse into self-watching. They aim it outward, toward the task, the data, the individual under care, or the audience. At the brain level, this keeps resources flowing to networks that support problem-solving and away from networks that generate self-conscious worry. Because they have practiced this shift over and over, it happens quickly, almost without effort.

Third, they protect their introductory brain chemistry. Sleep, movement, and nutrition are not optional extras for them. They understand that chronic sleep loss, blood sugar swings, and constant stimulation push the amygdala into a more reactive state and weaken the prefrontal cortex. Many of my calmest clients are not perfect in these areas, but they are consistent. They build routines that keep their brain closer to a stable middle ground, so it takes more to tip them into anxiety.

Fourth, they rehearse failure in a very particular way. They do not pretend that everything will always go smoothly. Instead, they picture potential problems and imagine themselves handling them with skill. From a neuroscience perspective, this approach creates a library of mental movies in which things go wrong, but the story still ends with competence and recovery. When something similar happens in real life, the brain already has a template for staying engaged instead of shutting down.

Fifth, they usually have a different relationship with self-criticism. It is not that they are soft on themselves. Many of them hold very high standards. The difference is that their inner voice during pressure sounds like a firm but supportive coach, not an attacking critic. When they stumble, their first thought is often “adjust and continue,” rather than “you are a disaster.” This matters because harsh self-attack activates the same threat circuits that power performance anxiety. A calmer, more precise inner voice keeps those circuits from igniting with every minor error.

Finally, many of these high performers have done deep work on the stories underneath their drive. They have looked at why success matters so much, what they fear it proves or disproves about them, and how early experiences shaped those fears. This is where my background in clinical neuroscience and coaching comes in. When I map someone’s history, I am not only interested in their symptoms. I am interested in emotional learning, which teaches the brain what to expect from the world.

When high performers face those stories directly and update them, their nervous system receives a different message. They no longer believe that every performance is a verdict on their worth as a person. Pressure moments still matter, but they are not life-or-death tests of identity. That shift in meaning softens the grip of performance anxiety at an intense level.

The gap between you and the calm person is not mysterious when you consider all these factors. It is made of clear, practical brain habits. The difference lies in how they interpret bodily signals and where they put their attention. They also demonstrate a strong focus on maintaining their basic brain health. The way they rehearse both success and failure is significant. You can also influence the tone of their inner voice. They carry stories about who they are.

Each of these elements is something you can begin to influence. When you work on them systematically, you learn more than just how to get through the next big meeting. You are reshaping the core conditions that either feed or weaken performance anxiety. That is how you move from feeling at the mercy of your brain to feeling like a true partner with it, especially when the lights are bright and everyone is watching.

Life After Performance Anxiety: Building A New Default Setting

Clients often ask me if they will ever feel completely calm before and during high-stakes events. The honest answer is that some level of activation is normal and even helpful. Your brain is supposed to care about decisive moments. The goal is not to become numb. The goal is to have a nervous system that rises to the challenge and then settles, without getting stuck in a spiral of performance anxiety. In my work at MindLAB Neuroscience, the most effective approach to performance anxiety blends precise, brain based coaching with repeated practice in the real-life situations that matter to you.

As you train your brain, you begin to build a new sense of identity. Instead of seeing yourself as someone who always falls apart under pressure, you start to experience yourself as someone who can stay with discomfort and still perform well. This identity shift is not just a mindset trick. It reflects fundamental changes in your brain networks. The prefrontal cortex gains stronger connections to the amygdala. The insula learns to read sensations with less alarm. The autonomic nervous system knows that it can move up and down the ladder of arousal without tipping into panic.

Over months, and sometimes years, your brain creates a new default. High-stakes situations still bring energy, but they do not threaten your sense of self. You stop rehearsing every mistake in your head at night. You walk into rooms with a more profound understanding of readiness. You know that if performance anxiety shows up, you have tools to meet it. This confidence is not wishful thinking. It is grounded in repeated experiences in which you stayed engaged while your nervous system did something different from the old pattern.

This new default also changes how you set goals. When performance anxiety runs your life, you naturally avoid situations that might trigger it. You say no to promotions, speaking invitations, or personal conversations that matter. When your brain learns it can handle these states, your world opens up. You are more willing to step into stretch situations because you trust your ability to navigate them.

At MindLAB Neuroscience, I have seen clients go from avoiding any public speaking to leading global teams. I have seen people who could not have hard conversations in their relationships learn to communicate with clarity and warmth, even when their heart is beating fast. These changes are fundamental and result from respectful, science-based work with the brain. Performance anxiety becomes a single chapter, not the entirety of their story.

Bringing It All Together, Trusting Your Brain Under Pressure

Performance anxiety can appear as an adversary when you need to maintain stability. But when you look at it through the lens of neuroscience and evolution, it becomes something else. It becomes a protective pattern, built from old survival circuits, past experiences, and repeated choices. That pattern is powerful, but it is not fixed.

You have learned that evolution wired your brain to care deeply about social status and group acceptance. The same systems that once kept you alive in dangerous environments now misfire in conference rooms, on stages, in exam halls, and in intimate conversations. You have seen how key brain regions, like the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, insula, and autonomic nervous system, work together to create the experience of performance anxiety. You have also observed how neuroplasticity can either reinforce this pattern or create new avenues for response.

Most importantly, you now have a clearer sense of how to work with your own nervous system. You can start before the event, shaping your predictions through calmer preparation and realistic rehearsal. You can use breath and attention in the moment to keep the thinking parts of your brain online. You can interpret your bodily sensations as waves of sound energy, not as proof that you are broken. Each time you do this, you are teaching your brain something new.

As a neuroscientist and coach, my job is to help people build that new wiring in a precise and compassionate way. When you respect how your brain is built, you stop fighting against it and start guiding it. Performance anxiety no longer feels like a mysterious force. It becomes a pattern you understand and can influence.

You do not have to wait until you feel perfectly confident before taking action. Confidence grows from action taken while your nervous system is still learning. If you start to apply these brain-based ideas to your own life, even in small ways, you will give your brain the experiences it needs to change. Over time, you can move from fearing performance anxiety to seeing it as a signal that you are on the edge of growth and that your brain is ready for a new story.

#PerformanceAnxiety #Neuroscience #AnxietyRelief #BrainHealth #HighPerformers #MindLABNeuroscience