🎧 Audio Version

Every day, millions of people declare they want to change. They recognize the need for behavior change, understand the benefits, and genuinely desire transformation. Yet fewer than 30% will follow through. This paradox, the gap between wanting help and taking action, isn’t about laziness or lack of willpower. The neuroscience of behavior change reveals a more complex story involving hyperbolic discounting, dopamine dysregulation, and the intention-behavior gap that hijacks even the most motivated individuals.

Executive Summary

Most people can envision a better version of themselves. They understand intellectually what needs to shift in their lives, whether it’s health, relationships, career performance, or emotional regulation. They consume self-help content, research coaching programs, and even contact professionals. Yet when it comes time to invest the money, commit the time, or sustain the effort required for real behavior change, resistance takes over.

This isn’t moral failure. It’s neuroscience.

The human brain evolved to prioritize immediate survival over long-term optimization. The dopamine system, which is meant to maximize reward rate in uncertain situations, significantly undervalues future benefits. The amygdala, our threat detection system, interprets present costs like financial investment, vulnerability, and effort as certain losses, while benefits remain abstract and uncertain. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive function and goal pursuit, operates with limited bandwidth and can only manage a finite number of competing priorities.

Understanding the neuroscience of behavior change removes shame and replaces it with strategy. This comprehensive white paper explores the neurological, psychological, and economic barriers that prevent people from following through on their desire for growth. More importantly, it provides evidence-based solutions rooted in brain science, not generic motivation advice.

With over 25 years of clinical neuroscience coaching experience and a forthcoming book from Simon and Schuster on dopamine optimization, titled The Dopamine Code, this framework represents the intersection of cutting-edge research and real-world application. The goal is simple: help you understand why behavior change feels impossibly hard and give you the tools to make it neurologically inevitable.

The research is clear. Behavior change doesn’t require superhuman discipline. It requires understanding how your brain works and strategically aligning your approach with neuroscience. The dopamine system, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala don’t respond to willpower alone. They react to strategic intervention. When you work with your brain’s natural tendencies rather than fighting against them, sustainable behavior change becomes not just possible but inevitable.

The Neuroscience of Wanting vs. Doing: The Will and The Way

At the core of successful behavior change are two interactive but distinct brain systems that must work in harmony. Research identifies these as The Will and The Way.

The Will represents motivation and subjective value. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum encode the subjective value of goals and rewards. These regions ask, “How much do I want this?” The dopamine system, originating in the ventral tegmental area and projecting throughout the brain, assigns reward value to experiences and goals based on past learning and predicted future outcomes.

When you think about behavior change, such as starting an exercise program or hiring a coach, your ventromedial prefrontal cortex calculates whether the subjective value justifies the effort and cost. The challenge is that new behaviors lack a history of learned rewards. Your brain hasn’t yet experienced the dopamine hit from achieving the goal, so the subjective value starts low or even negative. Meanwhile, familiar behaviors like scrolling social media, eating comfort food, or avoiding difficult conversations are tagged with immediate, known reward value.

The Will represents your motivation level. But motivation alone doesn’t produce behavior change.

The Way represents executive function and implementation. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and associated executive function systems translate motivation into action. Executive function includes working memory, cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, and planning. These systems create action steps, manage competing priorities, override impulses, and sustain effort over time.

Critically, executive function operates serially, not in parallel. You cannot effectively pursue multiple complex, novel goals simultaneously. Your executive function is powerful but limited. Each significant effort requires fresh cognitive resources. When you deplete executive resources on one task, you have less available for others.

Reinforcement learning is the brain’s fundamental mechanism for behavior change. When a behavior produces a rewarding outcome, dopamine strengthens the neural pathway connecting the context, the action, and the reward. Over thousands of repetitions, behaviors become encoded in the dorsolateral striatum as habits. Habits require minimal executive function because they’re automated.

Old behaviors persist because they’re neurologically efficient. They’ve been rewarded repeatedly. They feel easy. New behaviors, by contrast, feel effortful because they lack this learned reward history and require sustained prefrontal cortex engagement.

Dopamine doesn’t just signal pleasure; it signals prediction error when an outcome is better than expected, dopamine spikes, strengthening the preceding behavior. When a result is worse than expected, dopamine dips, weakening the behavior. This is how the brain learns what’s worth pursuing.

Early in behavior change, outcomes rarely exceed expectations. You go to the gym once and don’t see immediate results. You have one coaching session and don’t feel transformed. The dopamine system learns: this experience isn’t as rewarding as I hoped. Without strategic interventions to create frequent small wins and immediate rewards, the behavior change effort collapses.

Contrary to popular belief, the feeling of effort isn’t ego depletion or a depleted willpower resource. Neuroscience shows that effort signals opportunity cost. The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex tracks the cognitive and physical cost of tasks. When the price of continuing a behavior exceeds the perceived value of alternatives, you experience effort.

This explains why behavior change feels harder when you’re worn out, stressed, or distracted. It’s not that your willpower is depleted; it’s that alternative behaviors like resting, scrolling, or snacking have increased in subjective value relative to your goal.

Long-term behavior change requires neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to form new neural connections. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is a protein that facilitates synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis. Exercise, sleep, stress management, and learning all increase this critical factor. Without adequate biological support, new behaviors struggle to consolidate into long-term memory and habits.

This is why capacity building in physical, mental, and stress regulation must precede ambitious behavior change goals. You can’t build new neural pathways on a depleted biological foundation.

Complex novel behaviors require both high skill and high motivation working together. When either dimension is weak, behavior change fails. When old behaviors have strong reward histories and new behaviors feel uncertain and effortful, the brain defaults to what’s familiar. This isn’t a weakness. It’s efficient neural processing optimized for survival, not growth.

The Cost-Benefit Paradox: Why Investment Triggers Fear

When someone balks at investing money, time, or vulnerability in coaching or therapy, they’re not being cheap or resistant. Their amygdala is performing a cost-benefit calculation that systematically biases against behavior change.

Loss aversion is one of the most robust findings in behavioral economics. Losses feel approximately 2.5 times more painful than equivalent gains feel pleasurable. When you consider spending money on coaching, your brain categorizes the expense as a specific, immediate loss. The benefit, improved performance or well-being, is abstract, uncertain, and in the future.

Money also represents safety and security. For many people, spending money, especially on intangible services like coaching, activates the amygdala’s threat response. Even when the investment is objectively affordable and the return on investment is high, the emotional weight of loss dominates decision-making.

Research consistently shows that executive coaching produces a seven-to-one return on investment on average. Yet knowing this intellectually doesn’t override the neurological bias against present loss.

The brain prefers the current state over alternatives, a phenomenon called status quo bias. At least I know what I have is the amygdala’s mantra. Change introduces uncertainty, which is often interpreted as a potential threat.

Even when the current state is suboptimal, with chronic stress, underperformance, or relationship dysfunction, it’s familiar. The brain has adapted. Behavior change means venturing into the unknown, which triggers fear circuitry regardless of logical analysis.

Beyond financial cost, people unconsciously calculate psychological costs. The vulnerability cost means if I invest in coaching and it doesn’t work, I’ll feel shame and embarrassment. I’ll have proof that I’m unfixable. The identity threat cost means seeking help requires admitting I can’t handle this alone, which conflicts with my self-concept as competent and independent.

The time cost creates concern. Behavior change requires sustained effort. What else could I be doing with that time? The opportunity cost feels enormous. The failure risk cost triggers worry that if I try and fail, I reinforce my negative self-concept. It’s safer not to try.

These hidden costs are rarely conscious, but they’re neurologically real. The amygdala processes them as threats and activates avoidance behavior.

The brain’s cost-benefit calculation is fundamentally flawed when it comes to behavior change. Costs are weighted in the present and treated as certain. Benefits are discounted hyperbolically over time and treated as uncertain. The mathematical formula the brain uses systematically undervalues future gains.

Investing in coaching may produce ten times the returns in career advancement, relationship quality, or mental health. Subjectively, the brain calculates a specific five-thousand-dollar loss now versus a vague, distant possibility of improvement later. Loss wins.

Rationally, financial investment should increase commitment through the sunk cost effect. I’ve paid for this, so I’ll show up and do the work. But before the investment is made, sunk cost works in reverse. People fear: What if I pay and then don’t follow through? I’ll have wasted the money and proven I can’t change.

Research also indicates that monetary incentives can reduce intrinsic motivation. When external rewards or external costs dominate, internal motivation weakens. If someone invests in coaching primarily to avoid wasting money rather than a genuine desire for growth, the behavior change is less likely to be sustained.

A senior executive contacted me about leadership coaching. He understood intellectually that improving his emotional regulation and communication skills would accelerate his career trajectory. He’d researched my credentials and approach. He agreed the fee was reasonable relative to his income.

Yet when it came time to sign the agreement, he hesitated for weeks. He described physical discomfort when thinking about the investment. His amygdala interpreted the cost as a threat to financial security, even though the amount represented less than half a percent of his annual income.

The cost-benefit analysis his brain performed wasn’t logical. It was neurological. We addressed this directly by reframing the investment as evidence of high self-worth and strategic intelligence, rather than financial risk. Once his amygdala understood the commitment as a strength signal rather than a threat, resistance dissolved, and genuine behavior change became possible.

Hyperbolic Discounting and Immediate Gratification: Why Tomorrow Never Comes

One of the most profound barriers to behavior change is hyperbolic discounting, a neurological quirk in how the brain values future rewards.

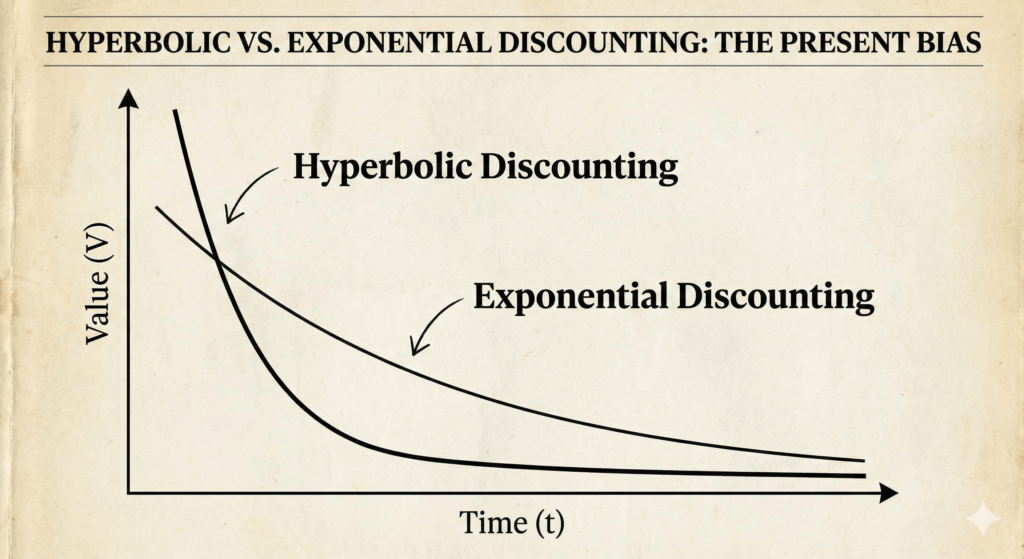

Standard economic theory assumes humans discount future rewards exponentially, meaning the value decreases at a constant rate over time. Neuroscience reveals that we actually use hyperbolic discounting: rewards lose value steeply at short delays, then the devaluation rate slows at more prolonged delays.

The subjective value of a future reward can be modeled as the reward value divided by 1 + the discount rate multiplied by the delay. The discount rate represents an individual’s impulsivity. Higher rates mean more impulsive, steeper discounting. Lower rates mean greater patience and ability to delay gratification.