🎧 Audio Version

Every day, millions of people declare they want to change. They recognize the need for behavior change, understand the benefits, and genuinely desire transformation. Yet fewer than 30% will follow through. This paradox, the gap between wanting help and taking action, isn’t about laziness or lack of willpower. The neuroscience of behavior change reveals a more complex story involving hyperbolic discounting, dopamine dysregulation, and the intention-behavior gap that hijacks even the most motivated individuals.

Executive Summary

Most people can envision a better version of themselves. They understand intellectually what needs to shift in their lives, whether it’s health, relationships, career performance, or emotional regulation. They consume self-help content, research coaching programs, and even contact professionals. Yet when it comes time to invest the money, commit the time, or sustain the effort required for real behavior change, resistance takes over.

This isn’t moral failure. It’s neuroscience.

The human brain evolved to prioritize immediate survival over long-term optimization. The dopamine system, which is meant to maximize reward rate in uncertain situations, significantly undervalues future benefits. The amygdala, our threat detection system, interprets present costs like financial investment, vulnerability, and effort as certain losses, while benefits remain abstract and uncertain. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive function and goal pursuit, operates with limited bandwidth and can only manage a finite number of competing priorities.

Understanding the neuroscience of behavior change removes shame and replaces it with strategy. This comprehensive white paper explores the neurological, psychological, and economic barriers that prevent people from following through on their desire for growth. More importantly, it provides evidence-based solutions rooted in brain science, not generic motivation advice.

With over 25 years of clinical neuroscience coaching experience and a forthcoming book from Simon and Schuster on dopamine optimization, titled The Dopamine Code, this framework represents the intersection of cutting-edge research and real-world application. The goal is simple: help you understand why behavior change feels impossibly hard and give you the tools to make it neurologically inevitable.

The research is clear. Behavior change doesn’t require superhuman discipline. It requires understanding how your brain works and strategically aligning your approach with neuroscience. The dopamine system, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala don’t respond to willpower alone. They react to strategic intervention. When you work with your brain’s natural tendencies rather than fighting against them, sustainable behavior change becomes not just possible but inevitable.

The Neuroscience of Wanting vs. Doing: The Will and The Way

At the core of successful behavior change are two interactive but distinct brain systems that must work in harmony. Research identifies these as The Will and The Way.

The Will represents motivation and subjective value. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum encode the subjective value of goals and rewards. These regions ask, “How much do I want this?” The dopamine system, originating in the ventral tegmental area and projecting throughout the brain, assigns reward value to experiences and goals based on past learning and predicted future outcomes.

When you think about behavior change, such as starting an exercise program or hiring a coach, your ventromedial prefrontal cortex calculates whether the subjective value justifies the effort and cost. The challenge is that new behaviors lack a history of learned rewards. Your brain hasn’t yet experienced the dopamine hit from achieving the goal, so the subjective value starts low or even negative. Meanwhile, familiar behaviors like scrolling social media, eating comfort food, or avoiding difficult conversations are tagged with immediate, known reward value.

The Will represents your motivation level. But motivation alone doesn’t produce behavior change.

The Way represents executive function and implementation. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and associated executive function systems translate motivation into action. Executive function includes working memory, cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, and planning. These systems create action steps, manage competing priorities, override impulses, and sustain effort over time.

Critically, executive function operates serially, not in parallel. You cannot effectively pursue multiple complex, novel goals simultaneously. Your executive function is powerful but limited. Each significant effort requires fresh cognitive resources. When you deplete executive resources on one task, you have less available for others.

Reinforcement learning is the brain’s fundamental mechanism for behavior change. When a behavior produces a rewarding outcome, dopamine strengthens the neural pathway connecting the context, the action, and the reward. Over thousands of repetitions, behaviors become encoded in the dorsolateral striatum as habits. Habits require minimal executive function because they’re automated.

Old behaviors persist because they’re neurologically efficient. They’ve been rewarded repeatedly. They feel easy. New behaviors, by contrast, feel effortful because they lack this learned reward history and require sustained prefrontal cortex engagement.

Dopamine doesn’t just signal pleasure; it signals prediction error when an outcome is better than expected, dopamine spikes, strengthening the preceding behavior. When a result is worse than expected, dopamine dips, weakening the behavior. This is how the brain learns what’s worth pursuing.

Early in behavior change, outcomes rarely exceed expectations. You go to the gym once and don’t see immediate results. You have one coaching session and don’t feel transformed. The dopamine system learns: this experience isn’t as rewarding as I hoped. Without strategic interventions to create frequent small wins and immediate rewards, the behavior change effort collapses.

Contrary to popular belief, the feeling of effort isn’t ego depletion or a depleted willpower resource. Neuroscience shows that effort signals opportunity cost. The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex tracks the cognitive and physical cost of tasks. When the price of continuing a behavior exceeds the perceived value of alternatives, you experience effort.

This explains why behavior change feels harder when you’re worn out, stressed, or distracted. It’s not that your willpower is depleted; it’s that alternative behaviors like resting, scrolling, or snacking have increased in subjective value relative to your goal.

Long-term behavior change requires neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to form new neural connections. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is a protein that facilitates synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis. Exercise, sleep, stress management, and learning all increase this critical factor. Without adequate biological support, new behaviors struggle to consolidate into long-term memory and habits.

This is why capacity building in physical, mental, and stress regulation must precede ambitious behavior change goals. You can’t build new neural pathways on a depleted biological foundation.

Complex novel behaviors require both high skill and high motivation working together. When either dimension is weak, behavior change fails. When old behaviors have strong reward histories and new behaviors feel uncertain and effortful, the brain defaults to what’s familiar. This isn’t a weakness. It’s efficient neural processing optimized for survival, not growth.

The Cost-Benefit Paradox: Why Investment Triggers Fear

When someone balks at investing money, time, or vulnerability in coaching or therapy, they’re not being cheap or resistant. Their amygdala is performing a cost-benefit calculation that systematically biases against behavior change.

Loss aversion is one of the most robust findings in behavioral economics. Losses feel approximately 2.5 times more painful than equivalent gains feel pleasurable. When you consider spending money on coaching, your brain categorizes the expense as a specific, immediate loss. The benefit, improved performance or well-being, is abstract, uncertain, and in the future.

Money also represents safety and security. For many people, spending money, especially on intangible services like coaching, activates the amygdala’s threat response. Even when the investment is objectively affordable and the return on investment is high, the emotional weight of loss dominates decision-making.

Research consistently shows that executive coaching produces a seven-to-one return on investment on average. Yet knowing this intellectually doesn’t override the neurological bias against present loss.

The brain prefers the current state over alternatives, a phenomenon called status quo bias. At least I know what I have is the amygdala’s mantra. Change introduces uncertainty, which is often interpreted as a potential threat.

Even when the current state is suboptimal, with chronic stress, underperformance, or relationship dysfunction, it’s familiar. The brain has adapted. Behavior change means venturing into the unknown, which triggers fear circuitry regardless of logical analysis.

Beyond financial cost, people unconsciously calculate psychological costs. The vulnerability cost means if I invest in coaching and it doesn’t work, I’ll feel shame and embarrassment. I’ll have proof that I’m unfixable. The identity threat cost means seeking help requires admitting I can’t handle this alone, which conflicts with my self-concept as competent and independent.

The time cost creates concern. Behavior change requires sustained effort. What else could I be doing with that time? The opportunity cost feels enormous. The failure risk cost triggers worry that if I try and fail, I reinforce my negative self-concept. It’s safer not to try.

These hidden costs are rarely conscious, but they’re neurologically real. The amygdala processes them as threats and activates avoidance behavior.

The brain’s cost-benefit calculation is fundamentally flawed when it comes to behavior change. Costs are weighted in the present and treated as certain. Benefits are discounted hyperbolically over time and treated as uncertain. The mathematical formula the brain uses systematically undervalues future gains.

Investing in coaching may produce ten times the returns in career advancement, relationship quality, or mental health. Subjectively, the brain calculates a specific five-thousand-dollar loss now versus a vague, distant possibility of improvement later. Loss wins.

Rationally, financial investment should increase commitment through the sunk cost effect. I’ve paid for this, so I’ll show up and do the work. But before the investment is made, sunk cost works in reverse. People fear: What if I pay and then don’t follow through? I’ll have wasted the money and proven I can’t change.

Research also indicates that monetary incentives can reduce intrinsic motivation. When external rewards or external costs dominate, internal motivation weakens. If someone invests in coaching primarily to avoid wasting money rather than a genuine desire for growth, the behavior change is less likely to be sustained.

A senior executive contacted me about leadership coaching. He understood intellectually that improving his emotional regulation and communication skills would accelerate his career trajectory. He’d researched my credentials and approach. He agreed the fee was reasonable relative to his income.

Yet when it came time to sign the agreement, he hesitated for weeks. He described physical discomfort when thinking about the investment. His amygdala interpreted the cost as a threat to financial security, even though the amount represented less than half a percent of his annual income.

The cost-benefit analysis his brain performed wasn’t logical. It was neurological. We addressed this directly by reframing the investment as evidence of high self-worth and strategic intelligence, rather than financial risk. Once his amygdala understood the commitment as a strength signal rather than a threat, resistance dissolved, and genuine behavior change became possible.

Hyperbolic Discounting and Immediate Gratification: Why Tomorrow Never Comes

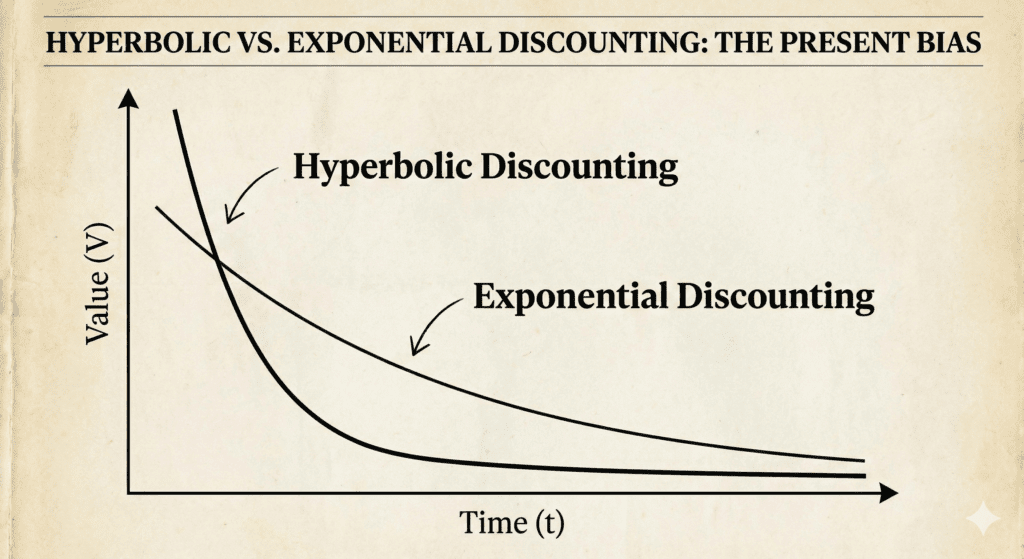

One of the most profound barriers to behavior change is hyperbolic discounting, a neurological quirk in how the brain values future rewards.

Standard economic theory assumes humans discount future rewards exponentially, meaning the value decreases at a constant rate over time. Neuroscience reveals that we actually use hyperbolic discounting: rewards lose value steeply at short delays, then the devaluation rate slows at more prolonged delays.

The subjective value of a future reward can be modeled as the reward value divided by 1 + the discount rate multiplied by the delay. The discount rate represents an individual’s impulsivity. Higher rates mean more impulsive, steeper discounting. Lower rates mean greater patience and ability to delay gratification.

Consider these examples of how hyperbolic discounting sabotages behavior change.

Consider the benefits of a gym membership for your future health. The benefit of improved fitness and reduced disease risk is months or years away. Your brain applies hyperbolic discounting, and the subjective value plummets. Meanwhile, the immediate discomfort of waking up early, physical exertion, and time commitment is undiscounted. The cost-benefit calculation favors staying in bed.

Scrolling social media provides immediate reward through novelty, social validation, and entertainment. Zero delay means zero discounting. The cost of wasted time and reduced productivity is in the future and heavily discounted. Your brain chooses scrolling.

Career coaching benefits, such as leadership skills, promotion, and higher income, are months away. Even though the absolute value is enormous, hyperbolic discounting reduces the subjective value. The cost of financial investment and vulnerability is immediate. Resistance wins.

This isn’t a character flaw. It’s evolutionary neuroscience. In ancestral environments, immediate rewards were reliably preferred to delayed, uncertain rewards. A berry in hand is worth more than the possibility of berries tomorrow when predators, competitors, and environmental uncertainty dominate survival.

Neuroscience research on dopamine reveals that the brain doesn’t just maximize absolute reward; it maximizes reward rate, meaning reward per unit time. This explains several behavior change phenomena.

When people invest consistent effort but see minimal returns, the brain calculates a low reward rate. Alternative behaviors that produce immediate small rewards have higher reward rates, so motivation collapses. This is why people give up when progress feels slow.

Quick wins are neurologically compelling because when you experience frequent small victories, the reward rate is high, and dopamine learning strengthens the behavior. This is why progress tracking, milestone celebrations, and incremental goals are so effective for sustainable behavior change.

Studies show that when the time between rewards lengthens, effort intensity drops. Your brain is optimizing reward rate, not just reward magnitude. Vigor decreases when intervals between rewards increase.

Understanding hyperbolic discounting doesn’t eliminate it, but it enables strategic countermeasures to support more effective behavior change.

Create immediate rewards. Don’t wait for the distant goal. Build in daily or weekly rewards for effort, not just outcomes. This keeps dopamine engaged and maintains subjective value throughout the behavior change process.

Progress tracking provides frequent reward moments. Each logged workout, each week of consistent effort, becomes a dopamine hit that supports continued behavior change.

External accountability through coaching check-ins or social commitments increases the perceived reward rate by making progress more salient and adding social reinforcement to behavior change efforts.

Visualizing your future self activates self-referential processing in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. When your future self feels psychologically connected to your present self, hyperbolic discounting decreases. The future becomes less abstract and more personally relevant, making behavior change more compelling.

The famous marshmallow test, which showed that children who delayed gratification succeeded later in life, isn’t purely about willpower. It’s about executive function capacity, learned trust in delayed rewards, and individual differences in hyperbolic discounting rates. Some people are neurologically wired for steeper discounting.

This phenomenon doesn’t mean behavior change is impossible for high discounters. It implies the strategy must account for this reality. Shorter time horizons, more frequent rewards, and external structure become essential components of successful behavior change.

The Intention-Behavior Gap Explained: When Wanting Isn’t Enough

Research consistently shows that only 30 to 40 percent of intentions translate into actual behavior change. This intention-behavior gap is one of the most frustrating realities of personal development. People genuinely want change, yet fail to act or sustain action.

The intention-behavior gap arises from five critical variables. For behavior change to occur, all five must align. If even one is missing or misaligned, the behavior collapses.

Internal motivation means I want to be healthier for myself. I value energy, longevity, and vitality. External motivation means my doctor says I need to lose weight. My spouse wants me to exercise.

Only internal, autonomous motivation predicts sustained behavior change. When goals are externally imposed, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which encodes personal value, doesn’t engage. Worse, external pressure can suppress activity in this region under negative feedback, making setbacks feel defeating rather than informative.

Autonomous goals protect motivation even when progress is slow. If the goal genuinely matters to you, temporary failures don’t collapse the entire effort. But if you’re pursuing someone else’s goal, every setback reinforces the thought, “I don’t really want this.” Actual behavior change requires internal alignment.

A trigger is an event or realization that prompts action. Practical triggers align with deeply held personal values. Ineffective triggers either conflict with personal values or depend on feelings of shame.

A person who values family connection might be triggered to improve their health after struggling to play with their kids. This aligns health with a core value, creating powerful motivation for behavior change.

Seeing an unflattering photo and feeling shame might trigger a diet attempt, but shame activates amygdala avoidance circuitry. The behavior is pursued to escape negative emotion, not to approach a valued outcome. This rarely sustains as a genuine behavior change.

Triggers without value alignment produce short-term bursts of motivation, followed by a collapse once the emotional intensity fades.

When you think about behavior change, what emotional response arises? A positive response sounds like, “I’m excited about who I’m becoming. I feel proud of taking this step.” A negative response might sound like, “I’m ashamed I let myself arrive at this point. I’m anxious about failing again.

Negative emotional responses lock dysfunctional behavior in place through amygdala dominance. Fear and shame activate avoidance circuits, making it neurologically difficult to approach the goal. Positive responses create approach motivation by engaging dopamine systems.

Refraining from ‘I’m overweight and unhealthy’ and saying ‘I’ve lost five pounds and I’m building momentum’ fundamentally changes the neural response. The brain learns: This behavior produces positive outcomes, and motivation strengthens, supporting continued behavior change.

Behavior change requires physical, cognitive, and emotional energy. Capacity is like a battery charge. When depleted, even strong intentions become irrelevant.

Capacity builders include adequate sleep, regular physical activity, stress management, time in nature, social connection, and gratitude practices. Capacity drains include chronic stress, poor sleep, sedentary lifestyle, social isolation, unprocessed emotional pain, and overcommitment.

Many individuals attempt to achieve ambitious behavior change goals while experiencing exhaustion. This is a neurological impossibility. Executive function, prefrontal cortex engagement, and sustained effort all require adequate biological capacity.

The solution: start with capacity-building goals first, even if they’re not your ultimate objective. Exercise, sleep hygiene, and stress reduction lay the foundation for other behavior changes.

Most behavior change goals are deceptively complex. “Be healthier” sounds simple, but unpacking it reveals nested sub-goals. Exercising regularly requires finding a gym, buying workout clothes, allocating time, learning exercises, and overcoming social anxiety about the gym environment. Eating better requires researching nutrition, meal planning, grocery shopping, cooking, and resisting social pressure to consume. Reducing stress requires identifying stressors, developing coping strategies, possibly seeking therapy, and setting boundaries at work and home.

Each sub-goal has its own sub-goals. The complexity overwhelms executive function. You experience this as confusion, procrastination, or the sense that this is too hard.

Process failures aren’t motivation failures. They’re planning failures. The goal is too abstract, the steps too complex, and the competing priorities too numerous. Effective behavior change requires radical simplification. Pick one micro behavior. Make it absurdly small. Build consistency. Then add complexity gradually.

The habit system located in the dorsolateral striatum favors established patterns. Intentions live in the prefrontal cortex. When contextual cues arise, like stress, fatigue, or social pressure, the habit system activates automatically. Your intention to behave differently requires active prefrontal override, which demands executive function.

If executive function is depleted, distracted, or overloaded by competing goals, the habit wins. This is why behavior change feels easy in calm moments with high executive function but collapses under stress, when executive function is depleted.

New behaviors also lack learned reward value. Until the dopamine system tags the new behavior with positive value through repeated rewarded experiences, the subjective value remains low. Your brain asks, “Why am I doing this difficult thing when the old behavior feels easier?” Genuine behavior change requires building new reward associations.

Finally, competing motivations create opportunity costs. If you want to exercise but also rest, scroll through social media, and spend time with family, the opportunity cost of exercise feels enormous. The effort signal intensifies, and motivation collapses unless the value of behavior change clearly outweighs alternatives.

Fear of Vulnerability and Asking for Help

One of the least discussed barriers to behavior change is the neurological threat response triggered by vulnerability and help-seeking.

Research revealed a striking finding: people consistently underestimate others’ willingness to help by about 50%. When someone asks for help, others are far more willing to assist than the asker predicts. Yet asking for help triggers profound discomfort, blocking behavior change.

Why? Because vulnerability triggers ancient survival circuits in the amygdala.

In ancestral environments, social rejection meant death. Humans evolved as intensely social creatures dependent on group membership for survival. Being ostracized from the tribe meant starvation, predation, and death.

The amygdala evolved to interpret social threats like rejection, judgment, and exclusion as life-or-death dangers. When you consider admitting you need help, seeking coaching, or acknowledging a struggle, the amygdala interprets this as potential tribal rejection. The threat response activates even though, logically, you know help-seeking is smart.

Admitting weakness conflicts with self-concept protection. Your brain has constructed an identity, and threats to that identity activate the same neural networks as physical threats. If your identity includes being competent, independent, and capable, then seeking help for behavior change threatens your sense of self.

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex encodes identity-linked values. When behavior change conflicts with identity, this region assigns low subjective value to the change. Your brain resists not because you would rather not improve, but because improvement threatens who you think you are.

Shame activates pain networks in the anterior cingulate cortex. The experience of shame is neurologically similar to physical pain. This phenomenon is why vulnerability feels so acutely uncomfortable. It’s not metaphorical pain. It’s processed as real pain in the brain.

Western culture elevates independence as the ultimate virtue. Embrace the challenge. Real success means doing it alone. Vulnerability is stigmatized as weakness. Self-reliance is elevated above strategic collaboration. Asking for help equals admitting inadequacy.

These cultural messages wire neural pathways that resist behavior change, requiring external support.

The self-help industry paradoxically reinforces shame. The underlying message: You’re broken, but purchasable solutions exist. This creates a shame consumption cycle that undermines intrinsic motivation for behavior change. Rather than fostering internal growth, it creates external dependency and reinforces the belief that you’re inadequate without constant external input.

Seeing others succeed can trigger inadequacy rather than inspiration. Social comparison activates self-judgment circuits. If they can do it, why can’t I? Rather than motivating behavior change, this comparison reinforces shame and avoidance.

Toxic positivity, the insistence on maintaining positive thinking at all times, dismisses legitimate barriers to behavior change. Just think positively; it invalidates struggle, adds another layer of shame, and suppresses the processing of real obstacles. When people can’t even stay positive, they feel double failure, further blocking behavior change.

The solution requires reframing vulnerability and help-seeking entirely. Vulnerability isn’t weakness. It’s courage. It takes more strength to admit struggle and seek support than to pretend everything is fine. Behavior change accelerates when vulnerability is embraced.

Help-seeking isn’t inadequate. It’s strategic intelligence. Elite performers, executives, and high achievers all leverage expertise through coaching, therapy, and mentorship. Seeking help is how you accelerate behavior change, not evidence of failure.

Investment in coaching signals high self-worth, not desperation. It means you value yourself enough to invest in growth. This reframe transforms the amygdala’s threat response into an approach response, supporting sustained behavior change.

The Effort Paradox: Why Work Feels Like Punishment

One of the deepest barriers to behavior change is that effort itself is fundamentally aversive. Even when we want outcomes, our brain treats sustained effort as costly.

Effort signals opportunity cost, meaning what you’re giving up by choosing this activity. The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex tracks the cognitive cost of tasks. The sense of effort signifies the threshold at which alternative activities surpass the value of the current one.

This isn’t ego depletion, which has been largely debunked. It’s not that you run out of willpower like a gas tank emptying. It’s that competing activities increase in subjective value the longer you sustain effort toward behavior change.

Behavior change requires repeated effort. Each repetition carries an opportunity cost. Your brain continuously calculates: I could be resting, socializing, eating, or consuming entertainment instead. When those alternatives feel more valuable than continuing the effortful behavior, motivation collapses.

The brain learns from this pattern. If behavior change feels hard consistently, the dopamine system tags it as low in reward value. Future attempts become even harder because the learned association is that this behavior equals a high cost and a low reward. Breaking this cycle requires strategic reward structuring to support behavior change.

Habit formation through striatal shift takes a minimum of 60 to 90 days. During this window, the behavior requires active engagement of the prefrontal cortex, which feels effortful. Only after sufficient repetition does the dorsolateral striatum encode the behavior as automatic, reducing the perceived effort and making behavior change sustainable.

Accountability means external monitoring, which can trigger psychological reactance. Reactance is the brain’s resistance to perceived threats to freedom. Being watched activates performance anxiety circuits. People resist behavior change when it feels like surveillance rather than support.

Yet accountability dramatically increases the success rate of behavior change. The key is framing. When accountability is positioned as partnership and support rather than surveillance and judgment, reactance decreases and behavior change accelerates.

Many people believe they lack discipline and that, if they had more, behavior change would be easy. This is an illusion. The real issue isn’t discipline deficit. It’s competing subjective value calculations.

Alternative behaviors have higher immediate value. The solution isn’t to develop superhuman discipline. It’s to increase the subjective value of target behaviors and decrease the value of alternatives. Environment design, social commitment, and the structuring of immediate rewards all serve this goal, making behavior change feel less effortful.

Implementation intentions reduce perceived effort by creating automatic if-then plans. When X happens, I do Y. This method reduces the number of decisions required, preserving executive function and increasing the likelihood of behavior change.

Habit stacking leverages existing neural pathways by linking new behaviors to established habits. After I pour my morning coffee, I will meditate for two minutes. The established habit serves as a cue, reducing effort and supporting behavior change.

Environmental design eliminates effortful decisions. If healthy food is visible and junk food is hidden, you don’t need to exert willpower. The environment does the work, making behavior change automatic.

Small wins build momentum by reducing perceived effort over time. Each small success strengthens the neural pathway and increases subjective value, making future efforts feel easier and supporting sustained behavior change.

Self-Sabotage and Limiting Beliefs: The Internal Opposition

Self-sabotage isn’t a weakness or a character flaw. It’s a survival mechanism that protects outdated self-concepts, blocking behavior change.

Self-sabotage appears as negative core beliefs about capability. I’m not the type of person who succeeds at this. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex encodes identity-linked value. When behavior change conflicts with identity, this region assigns low subjective value to it. Your brain resists change that threatens your sense of self, even when it would benefit you.

Childhood conditioning creates behavioral templates that persist into adulthood. Early experiences wire the amygdala’s threat responses, which activate automatically. A person whose parents experienced financial stress may develop adult money anxiety that blocks investment in coaching, therapy, or behavior change programs despite having adequate resources.

These aren’t conscious choices. They’re automated neural responses learned early and reinforced over the years. Behavior change requires identifying and updating these patterns.

Fear of success can be as powerful as fear of failure. Success might mean outgrowing your social circle, increasing expectations and pressure, or becoming more visible and vulnerable to judgment. The amygdala interprets these outcomes as threats, activating avoidance circuits that sabotage behavior change.

Fear of visibility means that as you grow, more people notice you. Increased visibility brings increased scrutiny. For people with shame histories or social anxiety, the prospect feels threatening. The brain sabotages behavior change to maintain safety through obscurity.

Fear of failure means attempting behavior change, and failing confirms negative beliefs. It’s safer not to try than to gather evidence that you’re inadequate. This keeps people stuck in the status quo, avoiding behavior change that might disprove limiting beliefs.

All these fears activate amygdala avoidance circuits, making approach behavior neurologically difficult.

Attempts to control outcomes through rigid perfectionism actually create resistance. Paradoxically, trying to control everything depletes executive function and reduces flexibility, making behavior change harder.

Rigid control attempts create all-or-nothing thinking. If I can’t do it perfectly, I won’t do it at all. This mindset prevents behavior change by setting impossibly high standards that guarantee failure.

A growth mindset, characterized by flexibility and a learning orientation, predicts success over a fixed mindset. A growth mindset frames setbacks as information, not an indictment. This type of mindset protects motivation and supports continued behavior change despite obstacles.

Common self-sabotage patterns include procrastination as a form of threat avoidance, excuse-making as self-handicapping, perfectionism creating impossibly high standards that ensure failure, self-criticism reinforcing a negative self-concept, and isolation to avoid accountability.

These patterns aren’t character flaws. They’re protective mechanisms. The brain is trying to keep you safe from perceived threats. Behavior change requires compassionate dialogue with resistance rather than self-judgment.

The brain uses past data to predict future outcomes. If you’ve failed at behavior change repeatedly, your brain predicts, “I always fail at this.” The result becomes self-fulfilling. You unconsciously behave in ways that confirm the prediction because the brain seeks consistency.

Confirmation bias reinforces existing beliefs by selectively attending to information that confirms what you already believe. If you think you can’t change, you’ll notice every setback and dismiss every success, perpetuating the belief and blocking behavior change.

Neuroplasticity allows belief revision, but it requires repeated counter-evidence. You can’t think your way into new beliefs. You must behave your way into them through small, repeated successes that gradually rewrite the predictive model.

Effective behavior change requires identifying sabotage patterns without judgment, dialoguing with resistance to understand what it’s protecting, engaging in compassionate self-inquiry rather than self-criticism, conducting small behavioral experiments to gather new data, and seeking professional guidance to navigate blind spots.

A coach or therapist serves as an external observer who can identify patterns you can’t see in yourself. This outside perspective accelerates behavior change by interrupting automatic sabotage cycles.

Cultural Conditioning and Status Quo Bias

The brain prefers the current state over alternatives, even when choices are objectively better. This status quo bias is one of the most potent barriers to behavior change.

Loss aversion means losses loom larger than gains. Changing from the status quo feels like losing what you have, even when it is suboptimal. The brain weighs this loss more heavily than potential gains, blocking behavior change.

The endowment effect means we overvalue what we already possess. Current habits, beliefs, and patterns feel more valuable simply because they’re ours. New behaviors feel less useful because they’re not yet owned. This bias systematically favors the status quo over behavior change.

Regret avoidance means fear of buyer’s remorse. What if I invest in behavior change and regret it? This fear keeps people stuck in familiar patterns rather than risking change.

Cognitive ease suggests that familiarity is perceived as safety, which in turn is equated with goodness. The brain interprets ease of processing as a signal of truth and value. Because current patterns are familiar, they feel right. New patterns require cognitive effort, which the brain interprets as wrong or risky, resisting behavior change.

Cultural programming reinforces neurological biases against behavior change. The independence narrative teaches that real success means doing it alone. Vulnerability is stigmatized as weakness. Self-reliance is elevated above strategic collaboration. Asking for help equals admitting inadequacy.

These cultural messages create neural pathways that resist seeking support, a critical component of successful behavior change for most people.

The self-help industry creates a paradox. The message: You’re broken, but purchasable solutions exist. This creates a shame consumption cycle. You buy the book, the course, the program, hoping to correct yourself. When it doesn’t work, you feel more broken, so you buy the next solution. The cycle undermines intrinsic motivation and reinforces external dependency rather than fostering genuine behavior change.

Social proof can backfire when seeing others succeed triggers inadequacy rather than inspiration. Social comparison activates self-judgment circuits. Instead of thinking, “If they can do it, so can I,” people often think, “Why can’t I?” This reinforces shame and avoidance, blocking behavior change.

Toxic positivity dismisses legitimate barriers. Just thinking positively invalidates struggle, creating an additional shame layer. When people can’t maintain positivity during difficult behavior change, they feel double failure. This suppresses the processing of real obstacles, preventing strategic problem-solving.

Organizations resist change because it threatens established power structures, creates discomfort with new processes, triggers fear of unknown outcomes, and requires trust in change facilitators. These organizational dynamics mirror individual resistance at the collective level.

Breaking cultural conditioning requires normalizing help-seeking as strategic intelligence, reframing vulnerability as courage rather than weakness, challenging the independence mythology with the reality of interdependence, and distinguishing evidence-based beliefs from culturally conditioned assumptions.

Effective behavior change often requires explicitly identifying and rejecting toxic cultural narratives, then deliberately constructing new narratives aligned with neuroscience and evidence.

Neuroplasticity and The Path Forward: Your Brain Can Change

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. This is the biological foundation for all behavior change.

Synaptic plasticity is based on Hebbian learning principles, which state that neurons that fire together will wire together. Repeated behaviors strengthen synaptic connections between neurons involved in that behavior. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor facilitates long-term potentiation, the strengthening of synapses. The critical window for habit formation is 60 to 90 days, during which consistent practice rewires neural pathways to support behavior change.

Structural changes accompany behavior change. Gray matter density increases in brain regions associated with practiced skills. Strengthening white matter tracts improves the efficiency of neural communication. These changes require consistent practice, not just intention. You can’t think your way into a new neural structure. You must practice your way into it behaviorally.

Adult neurogenesis refers to the brain’s continued production of new neurons, particularly in the hippocampus. Exercise, learning, and stress management promote neurogenesis, providing the substrate for new behavior patterns. Depression and chronic stress suppress neurogenesis, making behavior change harder.

With practice, prefrontal cortex activation shifts earlier. Initially, you need effortful control in the moment of temptation. With repetition, the prefrontal cortex learns to activate earlier, in anticipation of challenge. Anticipatory control replaces reactive control, making behavior change less effortful over time.

The brain learns contextual cues that predict when control will be needed. This proactive shift is why habit formation eventually makes behavior change feel automatic. The context itself triggers the behavior without conscious effort.

Initially, new behavior change engages goal-directed systems in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and dorsomedial striatum. These regions require executive function and feel effortful. With repeated rewarded behavior, control shifts to the habit system in the dorsolateral striatum.

Once the dorsolateral striatum encodes the behavior, it runs automatically with minimal executive function required. This is why habits are so powerful for sustained behavior change. They bypass the effort and decision fatigue that collapses motivation.

Habits are context-specific. A person might exercise consistently at their home gym but fail to maintain the behavior when traveling. Generalization requires varied practice across multiple contexts to build robust behavior change.

Windows of enhanced plasticity occur during and after exercise when brain-derived neurotrophic factor is elevated, during sleep when memory consolidation occurs, in novel environments when novelty seeking activates dopamine, and during moderate emotional arousal. Extreme stress impairs plasticity, but moderate arousal enhances learning and behavior change.

Executive function capacity is relatively fixed. Training in one domain doesn’t generalize well across tasks. Improvement requires domain-specific practice. This means you can’t just develop general willpower or discipline. You must practice the specific behavior change you want to achieve.

Patience is essential. Neuroplasticity takes time. The brain doesn’t rewire overnight. Expecting immediate transformation sets up failure. Sustainable behavior change requires maintaining practice through the plasticity window, typically 60 to 90 days at a minimum.

Focus on one behavior change at a time because bandwidth is limited. Trying to change everything simultaneously overloads executive function and guarantees failure. Sequential behavior change succeeds where simultaneous change fails.

Create specific implementation intentions using when-then plans. When I wake up, I will meditate for five minutes. Specificity reduces decision fatigue and makes behavior change more automatic.

Leverage contextual cues for habit formation. Use the same time, place, and preceding action to trigger the new behavior. Consistency of context accelerates neural encoding and behavior change.

Reward small wins to engage dopamine learning. Don’t wait for the final goal. Celebrate every instance of the behavior, regardless of outcome. This builds positive associations and supports sustained behavior change.

Sustain practice through the plasticity window. The first 60 to 90 days are critical. Missing days disrupts neural consolidation. Consistency matters more than intensity for long-term behavior change.

Use coaching or accountability to maintain consistency. External structure compensates for limited internal executive function. A coach serves as an auxiliary prefrontal cortex, helping you maintain behavior change when motivation wavers.

Solutions Framework: Bridging the Gap From Neuroscience to Action

Techniques for creating sustainable behavior change don’t require superhuman discipline or willpower alone; they require understanding how your brain’s dopamine system, amygdala threat response, and executive function limitations actually work, then strategically aligning your approach with neuroscience instead of fighting against it. Understanding why behavior change is hard doesn’t automatically make it easy. Knowledge must translate into strategy. This section provides evidence-based interventions rooted in neuroscience.

Connect goals to core identity and values. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex encodes value for goals aligned with your identity. When behavior change aligns with your deepest values, motivation is sustained even through obstacles.

Ask: Why does this matter to me? It doesn’t matter to my doctor, spouse, or society. It matters to me personally. If the answer connects to your values, the behavior change will persist. If it does not, please consider identifying a different goal or reframing the current one to better align with your actual values.

Internal motivation predicts sustained behavior change where external motivation fails. Self-affirmation exercises, where you write about your core values and how the behavior change serves them, strengthen commitment and protect motivation during setbacks.

Vulnerability isn’t weakness. It’s courage. Reframe help-seeking as strategic intelligence rather than as a sign of inadequacy. Elite performers leverage coaches, mentors, and therapists. Seeking support accelerates behavior change.

Investment signals high self-worth, not desperation. When you invest in coaching or therapy, you’re saying, “I value myself enough to invest in growth.” This reframe transforms the amygdala’s threat response into an approach response.

Model your behavior on elite performers who all have support systems. Nobody achieves sustained excellence alone. Behavior change accelerates when you leverage expertise and accountability.

Create immediate rewards for long-term goals. Don’t wait for the distant outcome. Build daily or weekly rewards for effort, not just results. This keeps dopamine engaged and maintains subjective value throughout behavior change.

Daily and weekly milestones provide frequent dopamine hits. Celebrate every instance of the behavior, every week of consistency, and every small win. Such reinforcement builds positive associations and prevents motivation collapse.

Progress tracking makes gains visible. Use a journal, app, or chart to visualize progress. Each data point becomes a reward moment that strengthens behavior change.

Future self-visualization activates self-referential processing in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Spend time vividly imagining your future self benefiting from current behavior change. When your future self feels real and connected, hyperbolic discounting decreases and motivation strengthens.

Start with capacity building before pursuing ambitious behavior change. Exercise, sleep hygiene, and stress reduction create the biological foundation. Without adequate capacity, behavior change efforts will collapse regardless of motivation.

Use the smallest viable behavior. The two-minute rule suggests starting so small it feels trivial. Want to build an exercise habit? Commit to two minutes. This reduces resistance and creates consistency, which is more important than intensity for behavior change.

Reduce decision fatigue through environment design. Make desired behaviors easy and undesired behaviors hard. If you want to eat healthier, put healthy food at eye level and hide junk food. Does the behavior change work for you?

Build momentum before increasing difficulty. Focus on mastering the small behavior initially. Let it become automatic. Then gradually increase intensity or duration. This prevents overwhelm and supports sustainable behavior change.

External monitoring increases the perceived reward rate. When someone else tracks your progress, the behavior becomes more salient. Social accountability activates social bonding circuits, adding emotional reward to behavior change.

A coach serves as an auxiliary prefrontal cortex. When your executive function is depleted, your coach remains available. This external structure maintains behavior change when internal motivation wavers.

Regular check-ins create predictable reward moments. Knowing you’ll report progress to your coach creates positive pressure and milestone moments that support sustained behavior change.

Break complex goals into single, actionable steps. Don’t tackle everything at once. Identify the one following action and do only that. Simplicity preserves executive function and makes behavior change feel achievable.

Address one variable at a time. If motivation is low, work on value alignment before worrying about process. If capacity is depleted, focus on capacity building before pursuing other behavior change goals.

Eliminate competing goals temporarily. You cannot effectively pursue multiple complex changes simultaneously. Choose the one behavior change that matters most right now. Achieve it. Then address others sequentially.

Use implementation intentions in the “when-then” format. After lunch, I will go for a ten-minute walk. This reduces decisions and makes behavior change more automatic.

Leverage existing habits through habit stacking. After an established behavior, add the new behavior. After I brush my teeth, I will do ten pushups. The existing habit cues the new behavior, making behavior change easier.

Use consistent context cues to trigger behavior: same time, same place, same preceding action. Context consistency accelerates habit formation and behavior change.

Reward each repetition to engage striatal learning. Every time you perform the behavior, acknowledge it. This builds the neural pathway and makes behavior change feel rewarding rather than punishing.

Sustain practice for at least 60 to 90 days. This is the neuroplasticity window for habit formation. Missing days disrupts neural consolidation. Consistency through this window transforms effortful behavior change into automatic behavior.

Schedule dedicated, distraction-free time for novel tasks. Executive function requires focused attention. Multitasking during behavior change depletes effectiveness and makes the behavior feel more complicated than necessary.

Practice serial processing by pursuing one priority at a time. Don’t split attention across multiple behavior change goals. Focus intensely on one, achieve automaticity, then address the next.

Recognize effort as an opportunity-cost signal, not a limit on willpower. When behavior change feels effortful, your brain is saying alternative behaviors have increased in value. Either increase the value of your target behavior through rewards and progress tracking, or decrease the value of alternatives through environment design.

Use strategic rest to prevent motivation depletion. Behavior change isn’t about constant striving. It’s about sustainable rhythm. Rest, recovery, and celebration are essential components, not obstacles to overcome.

Neurological assessment identifies which specific barriers are blocking your behavior change. Is it motivation, capacity, process complexity, hyperbolic discounting, or self-sabotage? Accurate diagnosis enables targeted intervention.

Dopamine-optimization strategies increase baseline dopamine levels through sleep, exercise, nutrition, and stress management. Higher baseline dopamine levels improve motivation and make behavior change feel more rewarding.

Prefrontal cortex-strengthening exercises such as meditation, cognitive training, and novel learning enhance executive function capacity, making behavior change easier over time.

Amygdala-regulation techniques, including breathwork, mindfulness, and somatic practices, reduce threat responses that block vulnerability and hinder behavior change.

Personalized behavior change protocols account for individual neurobiology, history, values, and context. Cookie-cutter approaches fail because every brain is different. Customization enables sustainable behavior change.

Professional support becomes essential when repeated self-sabotage patterns persist despite your best efforts, when high external pressure exists without internal motivation, when complex trauma histories interfere with change, when executive function deficits like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder limit capacity, or when you need structured accountability to maintain behavior change.

A skilled coach or therapist accelerates behavior change by providing an external perspective, identifying blind spots, offering accountability, and tailoring strategies to your specific neurobiology and circumstances.

Permission to Progress

The gap between wanting help and taking action isn’t a character flaw. It’s neuroscience. Your brain’s hyperbolic discounting, amygdala threat responses, and executive function limitations create genuine barriers to behavior change.

Understanding this removes shame and replaces it with strategy. Resistance is biological, not personal failure. The neuroscience of behavior change reveals that your struggle is regular, predictable, and solvable.

Small, strategic interventions leverage brain plasticity to rewire neural pathways. You don’t need superhuman discipline. You need neuroscience-informed strategies that work with your brain rather than against it.

Professional guidance addresses blind spots you cannot see in yourself. A coach or therapist accelerates behavior change by providing an external perspective, structure, and accountability when internal motivation wavers.

Sustainable behavior change is possible with the proper framework. The question isn’t whether you’re capable. The answer is yes. The question is whether you’re willing to leverage evidence-based approaches rather than continue relying solely on willpower.

If you recognize yourself in these patterns, you’re not alone. Fewer than 30 percent of people who want change actually follow through, not because they lack willpower, but because they lack neurologically informed strategies for behavior change.

Your next steps are clear. Assessment means identifying your specific barriers. Is it motivation, capacity, process complexity, hyperbolic discounting, or self-sabotage? Accurate diagnosis enables targeted intervention for effective behavior change.

Strategy means developing a neurologically aligned action plan. This is not a generic template but a customized approach that takes into account your brain, values, capacity, and context.

Support means considering professional coaching to navigate blind spots and maintain accountability. Elite performers don’t achieve excellence alone. Neither will you. Behavior change accelerates with the right support system.

Action means starting with one small behavior change this week. Not ten changes. One. Make it absurdly small. Build consistency. Let neuroplasticity do its work over 60 to 90 days. Then add the following behavior change.

The neuroscience is clear: your brain can change. Neuroplasticity is real. New neural pathways form with consistent practice. Old patterns can be overwritten. Behavior change is not only possible, it’s inevitable when you align your approach with how your brain actually works.

Thousands of executives, professionals, and high performers have transformed their lives not by trying harder, but by working smarter with neuroscience-based coaching. The dopamine system, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala don’t respond to willpower alone. They react to strategic intervention based on understanding.

Your resistance isn’t the problem. It’s the data telling you something needs to shift. When you decode what your brain is actually saying, behavior change becomes the natural outcome rather than a constant struggle.

The help-seeking paradox dissolves when you understand that vulnerability is courage, investment signals self-worth, and strategic support accelerates growth. The cost-benefit calculation shifts when immediate rewards support long-term goals. The intention-behavior gap closes when all five variables align: motivation, triggers, response, capacity, and process.

Hyperbolic discounting loses power when you build frequent reward moments and connect emotionally to your future self. The effort paradox resolves when you increase the value of target behaviors and decrease the value of alternatives through environment design and habit stacking.

Self-sabotage transforms from enemy to teacher when you dialogue with resistance and understand what outdated beliefs it’s protecting. Cultural conditioning and status quo bias weaken when you deliberately construct new narratives based on evidence rather than assumptions.

Neuroplasticity is your greatest ally for behavior change. Your brain is designed to adapt, learn, and grow throughout life. The capacity for change isn’t in question. The only question is whether you’ll leverage the right strategies to activate that capacity.

You have permission to struggle. Behavior change is genuinely challenging. Your brain evolved for survival in environments radically different from modern life. The neural pathways that served your ancestors often sabotage your contemporary goals.

You have permission to seek help. Nobody achieves sustained excellence alone. Asking for support is strategic intelligence, not weakness. Investment in coaching or therapy is evidence of high self-worth, not desperation.

You have permission to start small. You don’t need to transform everything immediately. One micro behavior, practiced consistently, rewires neural pathways. Small wins compound into profound behavior change over time.

You have permission to move forward, to invest in your growth, to leverage support, and to trust that your brain can change when you work with its natural mechanisms rather than fighting against them.

The neuroscience of behavior change removes the mystery and provides the roadmap. Your resistance makes sense. Your struggle is every day. Your transformation is possible. The path forward is clear. The only remaining question is whether you’re ready to take the first step.

#behaviorchange, #neuroscience, #motivation, #dopamine, #personaldevelopment, #executivecoaching